November

28, 2001 As the year 2001 draws to a close, preliminary data

banks

indicate that the global economy will have experienced a dramatic

slowdown

in the rate of growth this year compared to robust growth in

2000.

"GDP growth is now slowing in almost all regions of the globe,

accompanied

by a sharp decline in trade growth," reported the International

Monetary

Fund (IMF) in its World Economic Outlook (October 2001).

November

28, 2001 As the year 2001 draws to a close, preliminary data

banks

indicate that the global economy will have experienced a dramatic

slowdown

in the rate of growth this year compared to robust growth in

2000.

"GDP growth is now slowing in almost all regions of the globe,

accompanied

by a sharp decline in trade growth," reported the International

Monetary

Fund (IMF) in its World Economic Outlook (October 2001).

The global economic slowdown is accentuated by the terrorists

attacks

in the United States on September 11, the delayed economic recovery in

the United States from a recession that "officially" began in March,

weakening

demand and confidence in Europe, another recession in Japan, a decline

in information technology (IT) spending around the world, further

deterioration

of financial conditions for emerging markets (especially Latin

America),

and declining equity markets.

The outlook for 2002 is (as usual) uncertain. Most of the

prominent

economic forecasts for 2002 have recently been revised downward.

However, none are predicting a global recession or depression. The

actual

economic performance next year will depend upon the reaction of

consumers

to the events of 2001, their confidence in the future, the effects of

lower

interest rates worldwide, and the success of the various economic

stimulus

packages in some of the world's biggest economies.

The Global Economy

The global economy is comprised of 177 countries. However, the

largest 17 (about 10%) of those countries produce 75% of the world's

gross

domestic product (GDP). The United States alone accounts for 22%

of world output. Thus, only a few countries primarily determine

the

course of the global economy. Last year, those 17 economies grew

at a weighted average annual rate of 4.7 per cent. This year they

will have grown by a mere 2.5 per cent. Next year, most of them

are

projected to grow slower than 2.0 per cent.

The table below shows the real GDP, inflation rate, and unemployment

rate for the world's 17 largest economies. The United States is

expected

to grow by only 1.3 per cent this year compared to 4.1 per cent last

year.

China, the world's 2nd largest economy, will have increased production

by 7.5 per cent in 2001. It is the fastest growing economy in the

group. Japan, now in its fourth recession in a decade, will have

decreased production by -0.5 per cent in 2001. India, the world's

4th largest economy, is growing at 4.5 per cent this year. The

European

trilogy of Germany, France, and Italy will have increased production

this

year by 0.8, 2.0, and 1.8 per cent, respectively. Rounding out

the

top 7, the United Kingdom expects to see 2.0 per cent growth for the

year

2001.

Real GDP, Inflation, and Unemployment --

2000

and 2001

The Largest 17 Countries in the World

|

Flag

|

Country

|

% of

World GDP*

|

growth

2000

|

growth

2001

|

inflation

2001

|

unemployment

(latest month)

|

|

United States |

22.0

|

4.1 %

|

1.3 %

|

3.2 %

|

5.4 % (Oct)

|

|

China |

11.5

|

8.0 %

|

7.5 %

|

1.0 %

|

N.A.

|

|

Japan |

7.3

|

1.5 %

|

-0.5 %

|

-0.7 %

|

5.3 % (Sept)

|

|

India |

4.6

|

6.0 %

|

4.5 %

|

3.6 %

|

N.A.

|

|

Germany |

4.5

|

3.0 %

|

0.8 %

|

2.5 %

|

9.5 % (Oct)

|

|

France |

3.2

|

3.4 %

|

2.0 %

|

1.8 %

|

9.1 % (Sept)

|

|

United Kingdom |

3.1

|

3.1 %

|

2.0 %

|

2.2 %

|

5.1 % (Aug)

|

|

Italy |

3.1

|

2.9 %

|

1.8 %

|

2.6 %

|

9.4 % (July)

|

|

Brazil |

2.7

|

4.5 %

|

2.2 %

|

6.2 %

|

N.A.

|

|

Russia |

2.5

|

8.3 %

|

4.0 %

|

22.1 %

|

N.A.

|

|

Canada |

1.9

|

4.4 %

|

2.0 %

|

3.1 %

|

7.3 % (Oct)

|

|

Mexico |

1.9

|

6.0 %

|

0.8 %

|

6.3 %

|

N.A.

|

|

Spain |

1.7

|

4.1 %

|

2.7 %

|

3.6 %

|

13.0 % (Sept)

|

|

South Korea |

1.7

|

8.8 %

|

2.5 %

|

4.4 %

|

N.A.

|

|

Indonesia |

1.5

|

4.8 %

|

3.0 %

|

10.8 %

|

N.A.

|

|

Australia |

1.1

|

3.8 %

|

2.3 %

|

4.2 %

|

7.1 % (Oct)

|

|

Taiwan |

1.0

|

6.0 %

|

-1.0 %

|

0.1 %

|

N.A.

|

|

All 17 |

75.3

|

4.7 %

|

2.5 %

|

N.A.

|

N.A.

|

* Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) basis for GDP

conversions

to common (US dollar) currency.

Sources: IMF. World Economic Outlook (October

2001)

and The Economist Magazine (Nov 10-16 2001)

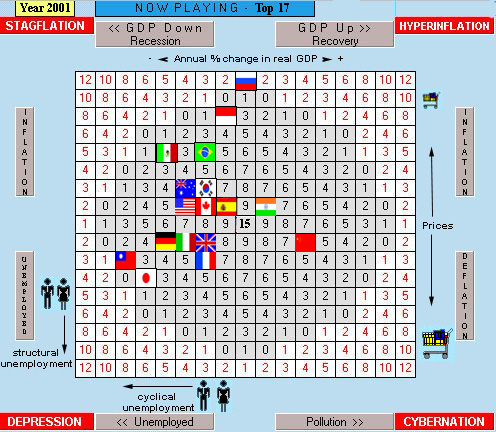

The visual image below depicts the playing field of The

Global

Economics Game and the relative economic performance of the

world's

largest 17 countries in 2001. The further to the right a

country/flag

is, the faster the rate of growth. The very center is

approximately

4 per cent real growth. When a country moves to the left of the

playing

field, the economy's rate of growth slows down and it can slip

into

recession (as in the case of Japan). Declining GDP causes

cyclical

unemployment. The higher up in the playing field a country goes, the

higher

the rate of inflation. For example, Russia's inflation rate is

22.1%.

The middle of the playing field is assumed to be approximately 2.5%

annual

inflation. Differences in the natural rate of unemployment for

different

countries can cause incongruities regarding inflation and unemployment

trade-offs. [Editor's note: The numbers in the playing field

indicate

a country's score as it attempts to balance growth, pollution,

inflation,

and unemployment. Black numbers are positive; red numbers are

negative.

The objective is to land in or near the center square. Placement of

countries

on the playing field based on IMF statistics is only an approximation.]

Source: IMF. World Economic Outlook (October 2001)

Output Gaps

It is clear from the image above that the major industrialized

economies

in the world have experienced a dramatic slowdown in their rates of

growth

in 2001. [They have moved to left side of the playing

area].

Virtually all of them have what economists call a recessionary output

gap.

An output gap is the difference between a country's actual GDP

and

its potential GDP. If the actual GDP is greater than an economy's

potential GDP (assuming a natural rate of unemployment), then the

economy

is experiencing an inflationary output gap. If the actual

GDP is lower than the economy's potential GDP, then the economy has a recessionary

output gap. The table below shows the IMF's estimated output gaps

for selected countries in the year 2001. The table shows, for

example,

that Japan's actual GDP in 2001 is 4.8% below its potential GDP.

Output Gaps: Selected Countries 2001

|

Australia |

-0.6

|

|

Canada |

-0.6

|

|

China |

-4.7

|

|

France |

-0.8

|

|

Germany |

-1.5

|

|

Italy |

-2.0

|

|

Japan |

-4.8

|

|

South Korea |

-2.5

|

|

Spain |

+0.0

|

|

Taiwan |

-4.9

|

|

United Kingdom |

-0.3

|

|

United States |

-0.5

|

Source: IMF. World Economic Outlook (October

2001)

Recessionary output gaps cause cyclical unemployment. More

workers

begin to lose their jobs as employers cut back production. On the

other hand, recessionary output gaps dampen the threat of

inflation.

It is clear from the economic data for 2001 that the world is more

concerned

about declining output and rising unemployment than it is concerned

about

inflation. Also, recessionary output gaps correlate with

declining

revenues and profits for business enterprises.

Equity Markets

The year 2001 has not been kind to equity markets. Stock

market

investors around the world have suffered losses this year. Three

notable exceptions are Mexico, South Korea, and Russia. The table

below shows the percentage declines (-) or advances (+) in selected

stock

market indices from December 31, 2000 to November 7, 2001.

Selected Stock Markets

% Change Dec. 31, 2000 to November 7, 2001

(in US $ terms)

| Australia (All Ordinaries) |

-6.2

|

| Brazil |

-39.4

|

| Britain (FTSE 100) |

-17.8

|

| Canada (Toronto Composite) |

-24.5

|

| France (SFB 250) |

-27.1

|

| Germany (Xetra DAX) |

-27.6

|

| Japan (Nikkei 225) |

-29.6

|

| Mexico |

+4.1

|

| South Korea |

+9.5

|

| Russia |

+44.7

|

| United States (DJIA) |

-11.4

|

| United States (Nasdaq Comp) |

-25.6

|

Source: The Economist Magazine (Nov.

10-16

2001)

The Wealth Effect and Consumer Confidence

Falling output, eroding profits, rising unemployment, and declining

stock prices undermine consumer confidence. The wealth effect

refers to how people behave when they suffer losses in wealth.

When

stock prices fall, for example, stock holders have experienced a

decline

in their net worth. When people feel poorer, they have less

confidence

and tend to spend less as consumers. Declining consumption

expenditures

can cause a recession or aggravate an economic slowdown. However,

confidence levels can sometimes be restored with deliberate simulative

economic policies.

Economic Policies -- Monetary and Fiscal

When market oriented economies experience an economic slowdown,

government

policy makers have essentially two choices. One is to do nothing

and wait for natural market incentives to bring about an economic

recovery.

This is called laissez faire policy -- leave the economy

alone.

A surprisingly large percentage of economists adhere to this school of

thought. To be fair, however, they advocate this policy

consistently

and are quick to point out that many recessions have been caused by

restrictive

economic policies (such as an overly tight monetary policy). If a

recession has been caused by ill-timed or overly restrictive policies,

then it would be necessary for government policy makers to correct

their

mistake.

The other choice for policy makers is to continually monitor and

actively

participate in the economy's overall performance. That is, for

example,

to undertake simulative policies when the economy slows down or falls

into

a recession. Most governments around the world seem to have adopted

this

thinking in response to the 2001 economic slowdown.

The two major economic policy tools available to governments are

monetary

and fiscal policy. Monetary policy refers to the control of

money,

credit, and interest rates. Fiscal policy refers to government

spending

and tax policy. Monetary policy has the advantage of rapid

implementation.

Independent central banks can act quickly. Monetary policy has

the

disadvantage of a long effect lag. That is, it can take a long

time

before the economy responds to a given monetary policy. Fiscal

policy

has the disadvantage of political gridlock. It can take a long

time

before budget bills and stimulus packages can work their way through a

democratic congress. Also, governments that are already

handcuffed

by a relatively large debt find it difficult to deficit spend.

Fiscal

policy has the advantage of a fairly rapid multiplier effect once

government

spending is actually increased and/or taxes are cut.

Monetary authorities around the world have been quick to respond to

the economic slowdown of 2001. They have added liquidity to their

economies, and interest rates have fallen dramatically for the past

year.

The table below shows per annum interest rates for 3-month money market

instruments on November 7, 2001 compared to the same rates one year

earlier.

The Federal Reserve Bank in the United States has been particularly

aggressive,

increasing the broad measure of the money supply by nearly 12% over the

past twelve months. The 3-month money market rate has fallen in

the

United States from 6.50% to 2.02%.

Interest Rates: 3-mth money market

(per annum)

|

Country

|

Nov. 7, 2001

|

Year Ago

|

| Australia |

4.22

|

6.38

|

| Britain |

4.00

|

6.06

|

| Canada |

2.20

|

5.68

|

| Denmark |

3.75

|

5.55

|

| Japan |

0.02

|

0.47

|

| Sweden |

3.57

|

3.98

|

| Switzerland |

2.04

|

3.50

|

| United States |

2.02

|

6.50

|

| Euro Area |

3.37

|

5.17

|

Source: The Economist Magazine (Nov.

10-16

2001)

Fiscal stimulus packages are also being implemented in Europe, the

United

States, Asia, and Latin America. The United States plans to spend

more on its war on terrorism, and an economic stimulus package

authorizing

more government spending and tax cuts is currently finding its way

through

the US congress. The United States has seen its budget surpluses

evaporate and is apparently willing to deficit spend to turn its

economy

around.

Outlook for the Year 2002

According to the IMF, "Substantial uncertainties and risks persist

[for

the year 2002], as the downturn makes the world more vulnerable to

further

unexpected developments, and a significant danger of a deeper and more

prolonged slowdown remains." However, if the combination of lower

interest rates, fiscal stimulus packages, and restored confidence were

to prevail, then the global economy could experience a mild economic

recovery

next year.

Sources and Recommended Links

http://www.imf.org/

http://www.economist.com/

Return

to Home Page Return

to World Economics News

The Global Economics Game (C)

2000

Ronald W. Schuelke All Rights Reserved