April

1999 The Japanese economy collapsed in 1998. The nation's

GDP

fell by 2.75% last year, and the unemployment rate rose to an

embarrassing

4.6% in February of this year. This is Japan's worst economic

performance

since the early 1970s, and there is little hope that the economy will

recover

quickly.

April

1999 The Japanese economy collapsed in 1998. The nation's

GDP

fell by 2.75% last year, and the unemployment rate rose to an

embarrassing

4.6% in February of this year. This is Japan's worst economic

performance

since the early 1970s, and there is little hope that the economy will

recover

quickly.

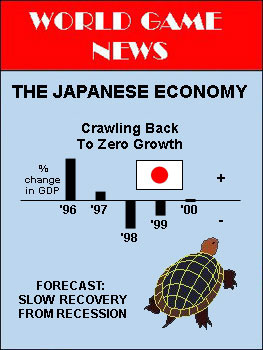

This month the International Monetary Fund (IMF) released its 1999 forecast for Japan. It predicted another 1.4% decline in GDP this year. Most other economic forecasts estimate that Japan would be doing well if it manages to stabilize production at zero growth by the year 2000.

In the late 1980s virtually no one predicted the collapse of the Japanese economy. Japan was riding a "bubble economy" with stock prices and GDP both ascending. Japanese management was said to be a model of efficiency, insightful government planning was credited with much of the nation's success, and the Japanese people were envied around the world for their industriousness.

Several reasons are cited to explain the recent reversal. Japan is still reeling from the deflationary effects which occurred when the "bubble economy" burst in the early 1990s. Stock prices and property values plummeted dramatically from their overly inflated values that had been driven up by greed and self-fulfilling, but short-lived, expectations. The inevitable bursting of the bubble set off a chain reaction of events which continues to weaken the current Japanese economy. The banking industry is plagued with a huge inventory of non-performing loans which are the direct result of reckless lending in the earlier period. Consumer and business confidence is very low. Pessimism has replaced optimism. That discourages spending and investment.

Contributing to the malaise were an ill-timed tax increase in 1997 and the collapse of other Asian economies which have cut back on their imports of Japanese merchandise. When you add all of the elements together, you get an Economics 101 textbook case of demand-side recession. A fall in aggregate demand causes production and prices to decline, and cyclical unemployment rises.

In his book, The General Theory (1936), the British economist John Maynard Keynes provided the world with a prescription for recessions and depressions which were caused by insufficient aggregate demand. His solution was to have the government deliberately initiate a fiscal stimulus package of government spending projects that would turn the economy around, even if it meant deficit spending. According to Keynes, the workers who were paid to complete the new projects would spend more when they got paid, and that spending would generate still more income to other households and workers who would spend still more. Thus, the government's initial spending would set into motion a multiplier effect of subsequent rounds of spending, and the economy would climb out of its recession.

Many world leaders have recommended that the Japanese government adopt the Keynesian model, and Japan has finally initiated a stimulus package of increased spending for public works projects along with some modest tax cuts and bank industry restructuring. However, there are good reasons to suspect that Japan's economic recovery will be slower than it might otherwise be.

For one, the stimulus package is necessarily modest, because Japan's national debt is already nearly 100% of its GDP and annual interest payments on its debt comprise nearly 25% of the federal budget. This prevents Japan from initiating major spending projects which might be necessary to accelerate a quick recovery. Also, unlike many other countries, Japan is somewhat precluded by its Constitution from spending a lot on military and national defense which can often jump start an economy. Furthermore, Japan has its own version and style of policy gridlock which involves civil service bureaucracy as well as political debate that can delay specific spending and tax programs.

Most importantly, the multiplier effect in Japan is almost assuredly very low and turtle-like slow. When consumer and business confidence are low and there is widespread fear of job loss, people refrain from spending and much of any extra income generated by a stimulus package is saved. The higher the marginal propensity to save, the weaker the multiplier effect.

Finally, monetary policy has been rendered almost impotent by the bad loans and economic conditions. Failing banks don't have money to loan, and even solvent banks have difficulty finding ready borrowers and justifying loans in a depressed economy. The Japanese monetary system may well be caught in what is called a liquidity trap. Interest rates in Japan are already close to zero, so they can't go down any further. The opportunity cost of holding idle cash balances is low, and deflation actually increases the purchasing power of money. When this occurs, increases in the money supply alone don't have much effect on production and employment.

An effective policy may require Japan to depreciate the yen. This would stimulate Japan's exports and curtail imports. Aggregate demand would increase, because Japanese products would be cheaper to foreigners. However, depreciating the yen would cause economic contraction in Japan's trading partner economies. They might retaliate with competitive currency devaluations of their own; and there are the negative feedback effects to consider, as well.

While most of Japan's problems are on the demand side, the government is not totally neglecting the supply side. Part of the stimulus package includes tax cuts aimed directly at business enterprises in Japan. The government is also deregulating retailing, oil importing, and the telecommunications industry. Deregulation often increases competitiveness and productivity, and it encourages private domestic investment. The combination of deregulation and currency depreciation would also encourage foreign investment in Japan, especially if there are early signs of returning optimism.

While no one is expecting the Japanese economy to bounce back quickly, there are some positive signs of potential for economic recovery. On April 23 the Japanese government claimed that the worst of the economic slump was over. The Economic Planning Agency (EPA) modestly boasted that Japan had "escaped the risk of a deflationary spiral." It reported that by the end of February, nearly 80% of Japan's $200 billion combined stimulus packages had been dispersed. Still, economic analysis suggests a painfully slow economic recovery for reasons cited above. Although actual economic performance has a way of humbling economic forecasts, it is likely that Japan won't return to a growth economy until after the year 2000. While a more rapid economic recovery is not inconceivable, it is unlikely.

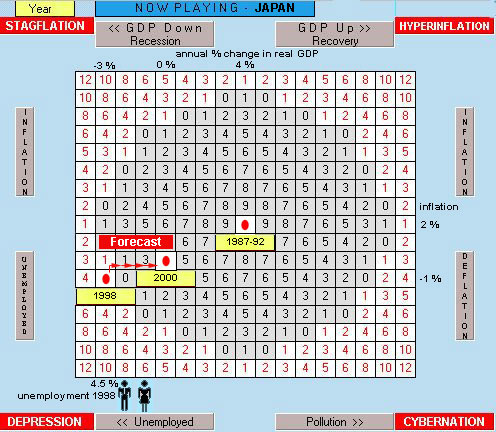

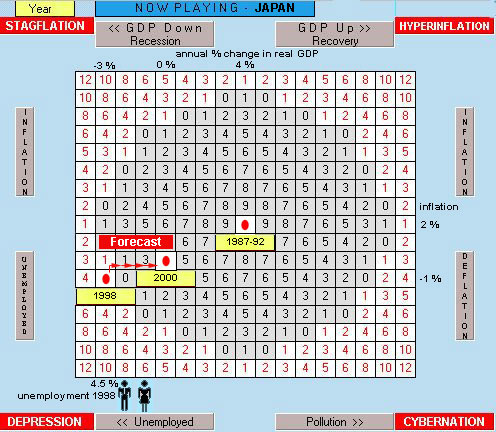

The picture above displays the playing field in The World

Game

of Economics. It shows that the Japanese economy

performed

ideally on average in the period 1987-1992. However, the 1998

recession

moved the nation's economy into the depression

area as production and prices fell, and cyclical unemployment

increased.

4.5% unemployment in Japan is more than twice their estimated natural

rate.

(Unemployment in Japan is currently higher than unemployment in the

United

States, which would have been thought virtually impossible several

years

ago, given the diverse structural and cultural composition of the two

countries).

Most forecasts estimate that Japan will do well if it can get back to

zero

growth by the year 2000.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|