May

1999 The United States is the world's biggest

economy.

Its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was $8.5 trillion in 1998! It is

also the world's largest trading nation. Because of its sheer

size,

the US economy plays a pivotal role in the performance of the global

economy.

Many nations are dependent upon continued export sales to the large US

market.

May

1999 The United States is the world's biggest

economy.

Its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was $8.5 trillion in 1998! It is

also the world's largest trading nation. Because of its sheer

size,

the US economy plays a pivotal role in the performance of the global

economy.

Many nations are dependent upon continued export sales to the large US

market.

The United States imports significantly more goods from the rest of

the world than it exports, and it has consistently done so since the

early

1970s. The US merchandise trade deficit was $ -248 billion in

1998.

It set a new record. A US trade deficit helps to increase the GDP

of other countries and creates jobs in their economies. Last

year,

the global economy receded in spite of growth in export sales to the

US,

but it was the strength of the US economy and the growth of its imports

which prevented the world from slipping into a more serious depression.

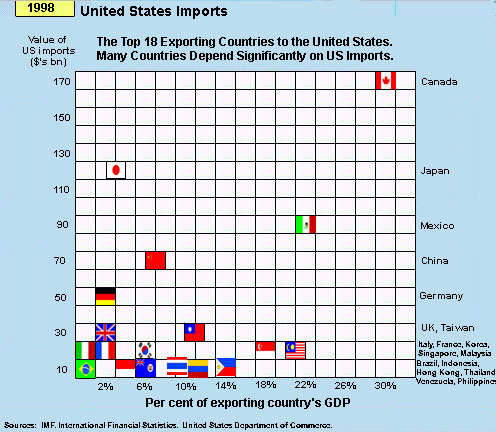

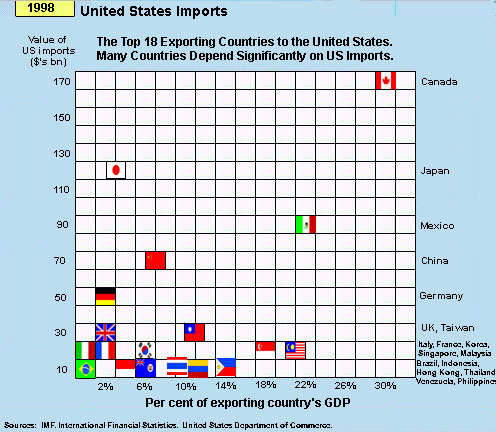

The picture below shows the degree to which many other countries in the world are dependent upon export sales to the United States to help their economies grow and prosper. For some countries like Canada and Mexico, exports to the United States represent more than 10 per cent of their GDP. For others, the percentage is not that high, but continued sales to the US is still very important.

In April of this year, the International Monetary Fund published its annual World Economic Outlook. Within that report, it posed this important question: "How Long Can the United States Remain the Engine of Global Growth?" Many others are asking themselves the same question, because if the US economy were to slip into a recession at this critical time, then the already stumbling global economy would fall on its face and suffer severe economic hardship. Japan and Brazil are already in recession. So are several other Asian economies. Russia and Indonesia are deep in stagflation, and the European economies are slowing down.

Intrinsically, the question is either self-evident or problematic, depending upon how one interprets it. It is better to divide the question into two separate and quite different ones, so that there is less confusion: (1) For How Long Can the United States Remain the Engine of Global Growth? (2) For How Long Will It? Economists know the answer to the first question. They don't know the answer to the second.

The answer to the first question is: "Indefinitely." That is, the US economy is capable of sustaining its internal growth and holding up the rest of the world with its imports for a very, very long time. That answer usually surprises some people. However, to understand why this is true, we need only examine the record of the United States balance of payments, which has chronically experienced a current account deficit since the early 1980s. A balance of payments is the financial accounting of a nation's international transactions that occur between itself and its trading partners. When a nation runs a current account deficit in its balance of payments, it simply means that the country is buying more than it is selling on current transactions including merchandise, services, investment income and unilateral transfers.

The United States runs a huge trade deficit on merchandise transactions. In 1998 it imported $919 billion in merchandise and only exported $671 billion. That's the main source of its current account deficit. The US actually exports more services (finance, medicine, education, other professional, entertainment, intellectual property rights, etc.) than it imports. However, (since 1997) it also pays more on its foreign liabilities than it earns on its foreign investments. And it gives approximately $40 billion away annually in net grants and transfers. The United States current account deficit was $ -233 billion in 1998.

When a nation runs a current account deficit, it must either (a) finance it through capital inflows (borrowing) from the rest of the world, or (b) sell some of its assets such as land, factories, and common stocks, or (c) draw down its reserves of gold and foreign exchange. The United States has been financing its current account deficits primarily by borrowing and transferring ownership of its assets to foreigners. Nearly 25 per cent of the US national debt, for example, is now held by foreigners and foreign institutions such as central banks.

The table below presents the United States balance of payments for

1998.

With few exceptions, it is fairly representative of the US experience

for

the past twenty years.

|

|

($'s billion) |

|

In |

| Merchandise Exports |

|

aircraft, machinery, and

agricultural products |

|

| Merchandise Imports |

|

oil, automobiles, and

consumer electronics |

|

| Balance of Trade |

|

||

| Net Services |

|

banking, education,

travel and entertainment |

|

| Receipts on US

Assets Abroad |

|

US bank deposits

held in other countries |

|

| Payments on Foreign

Assets in the US |

|

Foreign bank deposits

held in the US |

|

| Net Unilateral

Transfers |

|

"Thank You Notes" for

private and public gifts |

|

| Balance on Current Account |

|

||

| Exports of Capital

Assets & Liabilities |

|

land, factories, stocks,

and bonds (IOU's) |

|

| Imports of Capital

Assets & Liabilities |

|

land, factories, stocks,

and bonds (IOU's) |

|

| Statistical Discrepancy |

|

sum of other entries

with opposite sign |

|

| Liabilities to Foreign

Official Agencies |

|

US Treasury bills held

in foreign central banks |

|

| Change in Reserve

Assets |

|

gold, foreign exchange,

and SDRs |

|

| Overall Balance

of Payments |

|

Many people often ask: How can these trends persist? Won't the United States eventually go broke borrowing and buying all of that stuff from other countries? The answer is: "Not necessarily." The United States could continue this performance for a very long time. The reason turns on the nature of an economy and the potency of internally generated economic growth. Unlike the people who comprise them, economies are theoretically immortal. They can endure through time forever. Furthermore, there is no meaningful limit to the potential for growth over the long-run in mankind's universe. Growth is not zero sum. That is, as long as there are resources to be found, new technologies to be discovered, and better ideas than the last ones, then a country can experience sustained economic growth.

If the United States economy strikes that delicate compromise between spending and saving, adds to its infrastructure and capital stock, engages in research and development, expands the breadth and depth of knowledge, increases the productivity of its resources, and improves its international competitiveness, then it can continue to generate income and production capable of managing its foreign debt obligations and increase its standard of living at the same time. This reflects the power of compound growth. (Individuals could do this too, if they didn't get old and sick and tired and if they could perform numerous higher paid tasks simultaneously with skills continually acquired through education and training).

The more difficult, relevant and problematic question is for how long will the United States continue to be the engine of growth towing the rest of the world's economies. One of the foreboding lessons of economic history is that countries can recurrently suffer cyclical setbacks, which are capable of lingering for a decade or more. The Great Depression of the 1930s is an example. There's also a principle in mechanics which states that the more complex the machine, the more there is to go wrong or break. The global economy has evolved to an extraordinarily complex entity with highly sensitive and interdependent components, so that the chances of something going wrong and breaking down the system have increased. As some might remark, "It's downright scary when you begin to think about it!"

Without intending to be pessimistic or even to suggest that the system will necessarily break down (either because of the laws of probability or some other unknown reason), there are at least seven areas of concern in the current global climate which could conceivably go wrong. They each merit a brief discussion.

First, it's difficult to overstate the significance of market psychology and people's expectations in economics. This is not only true for highly speculative markets like commodity futures and equities, but it's also an important element in household decisions to spend and save as well as business decisions to incur risk and undertake expanding investments. The US economy has been bolstered by optimism in both the consumer and business sectors. Consumer spending increased by nearly 5 per cent in real terms in 1998. Real fixed investment in residential and nonresidential structures plus investment in producer durables jumped a whopping 11.4 per cent!. (Only business inventories fell, and that's a sign of strong retail sales). If the mood in these two sectors were to swing toward worry or pessimism or if the dynamics of cause-effect were to change, then consumer spending and business investment in the US could either slow down or decline outright. This U-turn would be devastating for both the US and global economy at this time.

Second, oil is still the world's principal source of energy. If its supply were disrupted either by OPEC's contrived production cutbacks or a military conflict, then the global economy would repeat the stagflation experience of the 1970s and early 1980s. Oil prices have recently climbed from a trough below $10 to $18 per barrel. Stagflation is especially painful, because all three of the major performance indicators (growth, unemployment, and inflation) are moving adversely. Stagflation is also frustrating, because conventional demand-side fiscal and monetary policies can only cure one (or two) of the three while causing the third one to become worse.

Third, there is a well respected school of economic thought which believes that business cycles are caused (rather than cured) by ill-conceived, wrongly timed, and over-reactive government policy making. According to this theory, when there is too much inflation (which may have been caused by previous excessive increases in the money supply), the government brakes the economy with an overly restrictive monetary policy. This, in turn, causes a recession. Policy gridlock then retards the reaction of fiscal policy to the recession, and monetary policy is rendered almost impotent in a deflationary spiral. Japan's recent experience is an example of latent and delayed fiscal policy, and its monetary policy effectiveness is about as low as its interest rates, which are asymptotically approaching zero. Whatever the origin of traditional demand-side recessions, they are recurrent but non periodic. Although a future recession is virtually a certainty, a full-blown depression is avoidable. Fiscal stimulus is the most direct policy cure. If governments can implement program and project spending quickly, demand-side recessions can be swiftly turned around.

Fourth, international finance has evolved to a highly sophisticated network. Large amounts of global funds now move from country to country rapidly seeking capital gains and higher real returns. Over $1.5 trillion in foreign exchange is traded daily! Capital flight has become a modern occurrence with increasing frequency. It causes severe disruption in the afflicted economy and sets off a chain reaction of panic and currency devaluations in other countries. Some think that capital flight is often irrational, based on incomplete information, and that it will become the main cause of economic instability in the future. Others believe that capital flight is merely a symptom of fundamental weaknesses in poorly managed and improperly structured economies. In either event, it is definitely a modern phenomenon and has the potential to affect the global economy for better and for worse. In this context, the biggest danger facing the global economy is the possibility that the US economy could experience capital flight. That would eliminate the United States' ability to finance its trade deficits. The US dollar would depreciate, imports would decline, and all those countries that depend on exports to the US would fall into recession.

Fifth, protectionism is one of the most perverse dangers in today's global economy. It is one of the first strategic policy considerations when a domestic economy goes awry. Countries use trade restrictions, tariffs, and currency devaluations in an effort to "export" their own internal problems, especially the visible problem of unemployment. There are still many proponents of import-substitution development strategy. This model defies the principle of comparative advantage. It recommends that countries identify what they are importing and then deliberately restrict those imports so that a domestic industry can be developed. The literature on this model is vast, and some of it is only a mouse click away on the internet's information highway. Arguments for protectionism, whether to solve a short-run cyclical problem or to implement a long-term development plan, gain more followers when an economy is not doing well. If the world were to become embroiled in an international trade war, all nations would lose. And there's a lot to lose in a highly interdependent global economy.

Sixth, as the summer of 1999 approaches, the war in the Balkans is very much on everyone's mind. Wartime economies are unique. That's why economists study them apart from normal, peacetime fluctuations. War, by its very nature, is destructive. It pollutes both the natural and social environments. Lives are lost, infrastructure is destroyed, shipments are disrupted, consumer goods are in short supply, information is censored, and the economy is managed by a chain of command. The prospect that the war in Kosovo will spread around the world is an "unthinkable" proposition. Military spending for war is often financed by printing money either during or immediately after the war. Historically, this has frequently been the underlying cause of hyperinflation. However, the Federal Reserve System is the independent monetary authority and central bank of the United States, and it doesn't even contemplate doing this.

Finally, the dynamics of technological change continue to threaten the job security of workers. That's what makes cybernation so bittersweet. Consumers benefit from better goods and services at lower prices. However, change disrupts the status quo. Some workers are able to ride the waves of change, while others are wiped out. They are often fired on short notice. Bewildered, they immediately wonder what they are going to do next to support their families. Structural unemployment is a problem, because the obsolete skills of workers don't match the new demands of the contemporary jobs market. Still, of all the things that could possibly go wrong with the US and the global economy in the future, this is probably the most benign. Structurally unemployed workers find new jobs relatively quickly in tight labor markets, and the United States has one of the best systems for adult education and training. Its network of community colleges and state university systems is second to none other in the world. Also, families and workers are surprisingly mobile in the United States. That diminishes the duration of structural unemployment.

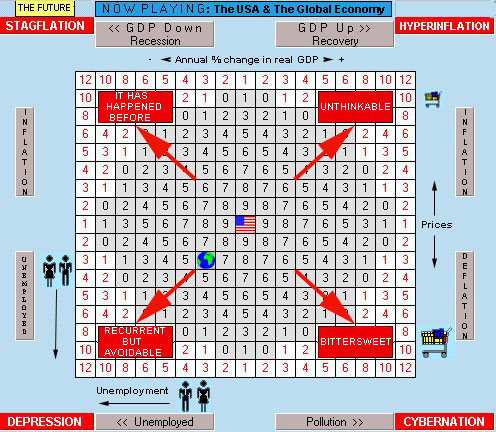

The display below shows the playing field of The World Game of Economics. It reveals that the US economy was in ideal balance regarding growth, pollution, unemployment, and inflation in 1998. It was tethered to the global economy by international interdependency, and in many ways kept the other economies from slipping further into recession and depression. Whether it will continue to do this or not is problematic. It has the potential for continued prosperity, but it can't perform much better than it did in 1998. That's precisely what makes a lot of people nervous about the future.