|

|

urHealdsburg.com |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

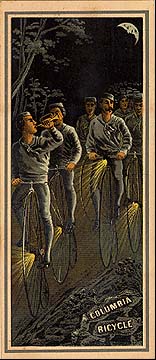

The Healdsburg Wheelmen "Bicycle run to Skaggs Springs, September 22,1895" Note the special jerseys with a HW logo. -- Healdsburg Museum photo

Bikers Become Outlaws: the Healdsburg Wheelmen

It may be difficult to imagine in an era of sleek sports cars and stomach-churning rocket rides just how racy the bicycle seemed in the 1890's. By 1899 there were 312 bicycle factories in the United States selling one million bicycles a year. Suddenly, so many people were spending their disposable income on

bicycles that other entertainment manufacturers, like piano makers, experienced a severe slump in sales. Daring young men and women (some of whom wore scandalous "bloomers"), middle aged folks, and just about anyone who could reach the pedals, wanted a bicycle, or a "Velocipede" as they were sometimes known.

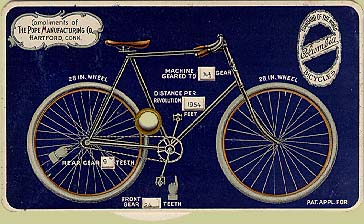

The first commercially successful American brand name bicycle was the "Columbia", manufactured by Colonel Albert A. Pope from about 1878 on. The Columbia looked much like the bicycle as we now know it, and incorporated the ball bearing and coaster brake. Another cycling innovation at this time was the "highwheeler", a bicycle with a larger front wheel (up to 5' high) that went at faster speeds, but might have been nicknamed the "bone breaker" for the rider's tendency to fall from such a height. Gradually further innovations, such as the addition of sprockets and solid rubber wheels, brought about the "safety bicycle", which most people rode by 1890.[1] For the next decade or two cycling was the king of sport and the preferred social setting for the young and the racy. The wild popularity of cycling actually brought about a great deal of national road improvements that later benefited the automobile. That cycling craze faded only when it was replaced by the new car craze beginning in 1900.

The first bicycles in Healdsburg were either home made or ordered through local retail outlets (usually hardware stores). It is not known how long significant numbers of Healdsburg cyclers were raising dust clouds on northern Sonoma County roads before some of them organized as the "Healdsburg Wheelmen" on April 10, 1895. Some of the founding members of the Healdsburg branch were Ben H. Barnes, W.R. Haigh, J.E. Ewing, A.W. Garrett, J.D. Hassett, J.B. McCutchan, and J.J. Livernash, editor of the Healdsburg Enterprise newspaper.[2] The national parent organization, the League of American Wheelmen, came into existence in 1881, and immediately began agitating for better American roadways. The parent club also founded the "Century Ride" (50 miles going, 50 miles back). The First Wheelman Meet

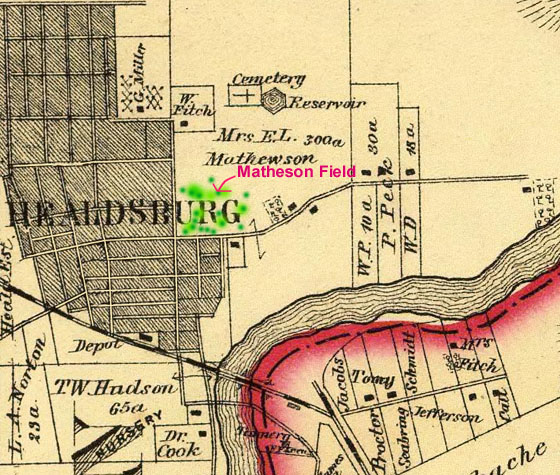

The first Healdsburg Wheelmen meet, held at the old Matheson Field on August 11, 1895, caused great excitement locally. An estimated crowd of 500 turned out to watch the strictly amateur cyclers avoid ruts and chuckholes on the track during eight breathtaking races. Local boy, Harvey Fuller, carried the day, winning the 1/8 mile, 1/4 mile, and 1/2 mile dashes, the last in one minute 25 and 4/5 seconds. Ellis Decker, a "Healdsburg crackerjack", was too fast to race, but did an exhibition half mile in an astonishing 1 minute 6 and 4/5 seconds. The only sour note came when Lou Goldman was accused of deliberately throwing his race with Quim Sewell because he bet heavily against himself before the race.[3] The second Wheelmen meet, on September 8, 1985, drew 1,000 spectators. Not all of the races were speed matches. The "slow race" was won by the last man over the finish line, and was meant to show grace, agility, and control. Even the speed races were friendly, as older cyclers were often given handicaps of a few hundred yards head start. Some of the "crackerjacks" were disqualified by the League as "professionals". Every attempt was made, it seems, to make the competition more a social than a real sporting event, although thrilled spectators witnessed several spectacular falls by determined racers.[4]

The third, and apparently final, Wheelmen race came on September 29, 1895. Frank Byne from San Jose, the Pacific Coast Speed Record Holder for the 1/2 mile (1:01 time), was on hand to observe. The prize for the most graceful rider that day went to Jack Haigh, but he had stiff competition from male riders who came dressed as women or in comical costumes. The Healdsburg Wheelmen set a local record that day for the mile run at 1 minute 10 and 3/4 seconds. (The minute mile was finally broken by "Mile a Minute Murphy" who rode behind a Long Island Railroad train in 1899. He did the mile in 57 4/5 seconds). The Tribune declared that the "Healdsburg cyclers...manifest a spirit of enthusiasm which those cities [Santa Rosa and Petaluma] have yet to show". Significantly, the hometown newspaper did not claim riding superiority.[5] We Don’t Care a RapThat Healdsburg "spirit of enthusiasm" may be what led the club into controversy later that same month. The League of American Wheelmen suspended local riders Charles Beard, Quim Sewell, Will Barnes, Harvey Fuller, Deventhal and others for taking part in the unsanctioned Healdsburg races. In response the spokesman for the rebellious club told the press, "We don't care a rap...and we will henceforth disregard and ignore entirely the dictations of the League." The Tribune stood behind the local Wheelmen, branding the League, "a despotic and imperious combination".[6]

The outlaw Healdsburg Wheelmen chapter stayed together as a group at least through the spring of 1896 when they were entertained by the Santa Rosa Wheelmen. The trip down the old dirt road to dinner at the Occidental Hotel was leisurely, as several ladies made up part of the convoy. At the same time the "Imperial Bikers" of San Francisco were also guests of the Santa Rosans.[7]

|

||||||||||||||||||||