This is really easy for me to say: I place a high value on honesty and fairness. Students who cheat are not honest and they are trying to place themselves ahead of others who have done honest work, which is not fair. I try to build a community (at the micro-level of the classroom as well as doing my part to improve the academic community at large) that is pleasant and functional in terms of educational opportunity, mutual trust, and credible, high-quality research. There is a converse effect: If I do not make the effort to discover and punish plagiarism and related issues, I am indirectly stating that the above values of honesty are not important enough to bother with. In other words, by caring, which is more or less automatic with me, I'm also forced to act because I don't like to live in a contradictory way. I don't really want to act, but the two are irreversibly linked. I'm jut not practical this way; it is in my nature to do what needs to be done rather than determine that it isn't practical to do so.

The above reasons would already be enough for me to care deeply about cheating. However there are two other reasons very important to me, really:

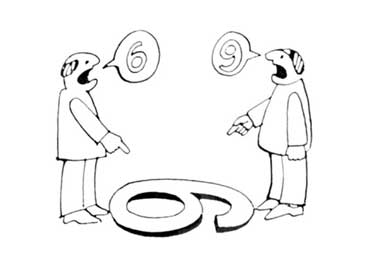

The first is that an effective (or maybe I should just say pleasant & satisfying?) student-teacher relationship is born of trust. All acts of academic dishonesty absolutely crush that trust. It is not that I regret the loss of the relationship with that particular student, although sometimes I do and sometimes we can even recover from it, but what really bothers me is that each event of cheating has an impact on students downstream; that is, it can cloud my ability to trust future students and definitely puts in place safeguards against similar events that future students must accept the burden of (see list below). Anyone who behaves in this way, at that particular moment anyway, has denied the obvious reality that we as humans form individual bonds and communities and share the same space even when we would like to think otherwise. It is impossible, in my mind, to control the distance that travels across place and time by your behavior. Students, when they cheat, conveniently forget this for that moment, thinking it is only more or less just between s/he and me. It is never that way; it is between you, me and the next several hundred students who will get measured with a memory of your behavior and have to shoulder the burden of the safeguards that you made necessary.

Second, I really want you to learn interesting things in my class; cheating, of course, short circuits that process — that’s obvious — but what might not be obvious is that it obscures my understanding of your understanding. I can’t tell any more what work is yours and what is just imported, and so on. Students can, and do, choose not to learn. But I am also free to try my best to teach you. Plagiarism and such really are a huge road block.

Third, cheating in all forms wastes my time. I am really very busy and a really resent having to take time to pursue such depressing matters as determining if a student has cheated and building a case against him or her and so on. You might think that I could just not worry so much about it but it is because I care about the honest students that I police for dishonesty: I want their environment to be safe and supportive and fair, and I will act against those who try to make it otherwise. But I still resent the time and students are cheated out of some time that could have been spent in better ways on them if the cheating had never happened.

Above all, the worst result is that I sometimes doubt students who do not deserve to be doubted. I try my best not to do this but it happens. I really regret that I have to think at all about this type of thing, or write these types of pages. The teacher student relationship can take two forms: we work cooperatively together discovering interesting ideas and each other for that matter, or I use the authority granted to me by the University to apply leverage to “persuade” you to do various things while you, using the tools available to you, attempt to un-leverage that pressure. The first is a beautiful relationship, one that I cherish; the other is truly depressing to me but a regular part of my job. Most educators have felt the burn of students who we were open and vulnerable to, trusting them, only to find out that they have cheated or otherwise taken advantage of the relationship. Many choose, at some point to distrust everyone, or most everyone, and all of us, I think, get more skittish over the years as the unpleasant events pile up. A student who cheats in a class of mine is remembered more or less permanently.

Academic dishonesty by students has lead to all sorts policies and practices created by me that lead to a more controlled and restricted classroom environment. Certain students have put all students in the same boat. Among changes I've implemented, though reluctantly and not without thought but because abuse happened too many times:

> the log in process is a result of student’s submitted corrupt files on purpose to try to get deadline extensions

> the late penalties are the result of students abusing frequently and severely less specific statements of deadlines, or deadlines without penalties … lateness was such a problem that there were times when class was almost dysfunctional — I was spending enormous time tracking down assignments, grading them at odd times and so forth

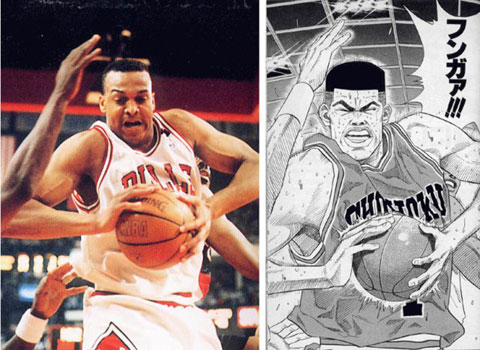

> the quiz process —both the speed of the timed slides and the “even” “odd” structure are the result of students taking answers from each other during the quiz. This quiz process works against non-native speakers, which I regret. I try to work with them individually to balance this out, and I have to spend much more time both making and grading the quizzes. The even/odd system is quite difficult to make. This is time I could spend better for the class

> no laptops is a result of students not keeping their word about using the laptop only for class

> seating charts was instituted after students cheated during a midterm and the only way I caught them was through a seating chart I secretly made during the exam since I sensed something wasn’t right. Seating charts are not a permanent part of my exams. Some students are uncomfortable where they are placed, all students have less time to write essay answers.

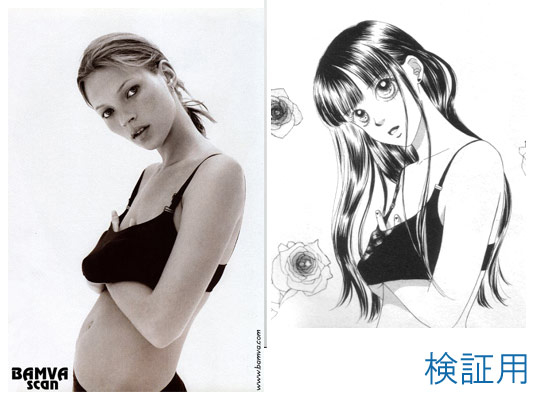

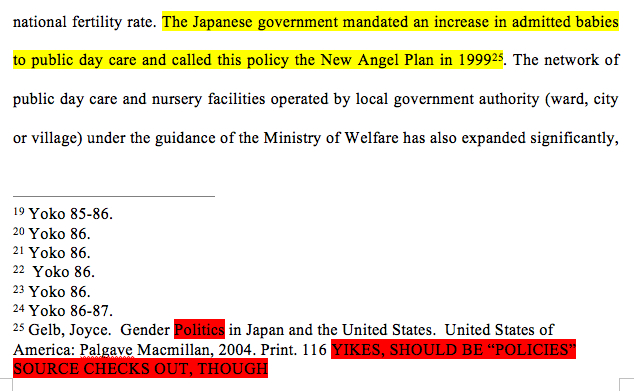

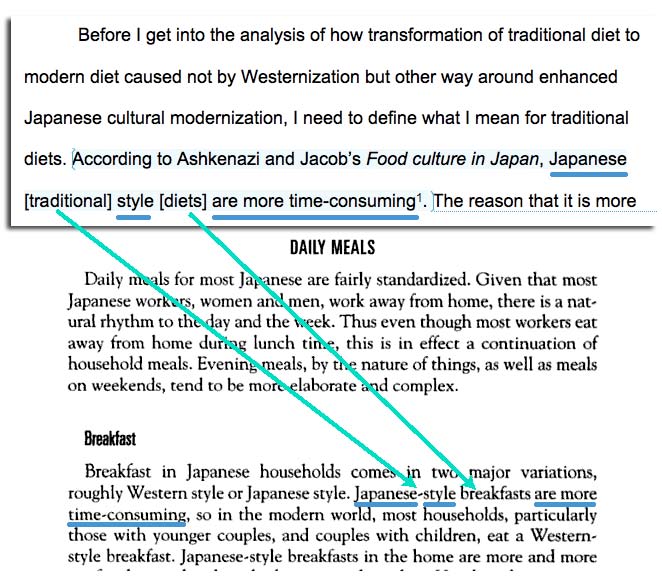

> essay bibliography abstracts began because students falsely listed sources they actually never had possession of

> essay source URL addresses is required so I can check footnotes

and so on.