|

Space Form and the Third Dimension

excerpted from the book Copies of this book can be obtained by clicking on the title above, or the book cover at the bottom of the page. Within this article, one can find their way out of the "box." The author articulates the organic synthesis of form and function to yield what can only be termed as simply expression. Construction is the developer's means of communication and contribution that works "with" and not only "for" the "Individual," but also the "Community." Build and Furnish. Inhabit and Create.-editor

The reality of the building does not consist of roof and walls but in the space within to be lived in.

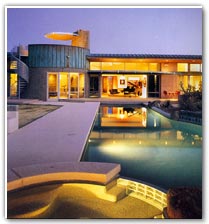

The advent of wrought iron, steel, and reinforced concrete made an enormous difference in the ability to create large, open spaces. The invention of plate glass brought light into buildings and allowed a visual connection between indoor and outdoor space. Yet despite these great new possibilities, architecture still tended towards box-like forms, rooms being just boxes within a bigger box. Wright pioneered the use these new materials and structural methods. As he did away with the box, in both plan and elevation, a new sense of space emerged, walls became screens and a sense of freedom entered architecture. Space no longer needed to be static and contained, but could flow freely. This idea of plasticity was new to architecture, though not to nature. Space serves the need of different activities, and buildings, except for some special-use types like warehouses, must respond to the dynamics of human movement and activity. A building is often very complex in terms of movement of people and goods, and an understanding of flow and function is basic. When Wright gave his view that Louis Sullivan's dictum, "Form follows function" should really be "Form and function are one," he was expressing the need for integration. "Design from within outward," said Wright, who once remarked that one of the first organic architects was Christ because he told us that "The kingdom of God is within you." In an organic design, the plan is an effective organization of space that accommodates the various functions of the building. The form of the building is a three-dimensional consequence of the plan. A building conceived as a three-dimensional entity will have design integrity. There is a natural hierarchy of space in architecture. In a house, for instance, the living area is naturally the dominant space, its form and mass clearly expressed on the exterior. Other spaces though subordinate, will interconnect and relate to each other. The integral flow of space and form are the essence of architecture. Central to the philosophy of organic architecture is the idea that there should be a sense of discovery of space. This discovery starts at the entrance to a building. Rather than scaling the front door of a building to a heroic scale to impress the person who enters, the entrances we design are usually underplayed. This is where the element of human scale is first established. The entrance should not lose anything in quality, but just as a good novel does not reveal its plot on the first page, the space experience becomes a series of discoveries as one progresses to the interior. Architecture is much more interesting if the arrangement of spaces is not too obvious, if there is a surprise and mystery around every corner. The unexpected space experience can add charm and appeal, so a space should seldom be seen in its entirety. Roofs and ceilings can have many levels; high, soaring spaces can be contrasted with low, snug alcoves. Bright, sunny space contrast with dark retreats, one interior space can borrow visually from other contiguous spaces through broad openings. Interior and exterior space can be separated by glass but linked visually so that interior space flows outwards. Walls can reach out and embrace the landscape. Spatial continuity and the continuous flow of space give architecture a magical sense of freedom. The elements that establish architectural space, the walls, roofs, and all the details, are given definition by their boundaries--by their edges and corners. In other words, they are defined by their terminals. Louis Sullivan passed along a wise observation, "Take care of the terminals and the rest will take care of itself." This applies not just to design but to many things in life. We only look well dressed if our shoes are shined, our fingernails are clean, and our hair is neat. A good opening and a good closing are keys to a successful talk or a story. So the design of corners, edges, and finials becomes important in the creation of space. Dimensions of an object have height, width and depth, but what do we mean by depth as an element of interior space? Depth in this case is not thickness but a dimension of space. It leads to the dynamics of space, what we might call spatial interweave, the interpenetration of one space into other spaces, the intersecting and overlapping of spaces. The lack of depth results in static, two-dimensional architecture. "Facade" buildings are, unfortunately, all too common. We often see them in tract housing, where the street elevation is "fancied up" with some brick or stone, but the sides and back are a sham, made of the cheapest possible materials. A shop that has only a "storefront" seems like a set for a western movie. The modern "glass box" office building is often just a mirrored shell that lacks depth. In organic architecture, space and form are three-dimensional. Walls become screens that define and differentiate space without confining or destroying it. The depth dimension is the quality that enables architecture to have that intangible but essential quality of spirituality. There is a mystery to nature and life that we seek to understand, but can never adequately describe. An organic building, in its third dimension, also has this magic, constantly bringing surprises of beauty. As the sun creates ever-changing patterns of light and shadow, different views of architectural forms and details reveal themselves. Light and shade give life to architecture. Most things in life we can learn, but it seems that a sense of artistic proportion is something with which we must be born. We can, however, augment whatever senses we have. A sense of proportion is essential to design, just as it is to life. In life, a sense of proportion will moderate our behavior, help us avoid excess. It will tell us when we have had enough to eat, the right amount of exercise and sleep that we need, and when we should stop talking. It applies to just about everything. In architecture, it will instinctively work to give proper balance to the sizes and shapes of spaces and forms. Harmony is only achieved when everything is in balance. A sense of proportion will help us avoid either underdoing or overdoing a thing. The great artist is the one who knows just when to stop.

The fairest thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and true science.

|

|