|

Home | Mountain Bikes | Fat Tire Flyer | Kelly Moving | APHIDS | Kelly Family | Sons of Champlin | Reprints | Links |

|

The Cundiff Saga: an oral history dictated by Susie Cundiff Patrick |

|

Around the turn of the 20th century, my great-grandparents travelled with their children from Missouri to Arizona, by way of Oregon. Their story is one of hardship and tragedy, and illustrates how tough life was for poor folks at that time. This was dictated to my mother, Frances [Blanke] Kelly, by her aunt, Susie Patrick, nee Cundiff, shown below in 1911. Below: Susie Cundiff in 1911

Frances Laura Blanke Kelly: "This story is written in memory of my mother, Lucy Frances Cundiff Blanke Monmonier, because I thought I could 'always' write down the stories she told me of the pioneer trek across western America. After her death, I found how faulty my memory was. It was then I had the opportunity to hear the story from Aunt Susie's lips. I have written it just as she told it to me while she visited me in the month of November 1976. She was recuperating from a fractured ankle, not yet ready to live independently in her own home. My sister, Helen, brought Aunt Susie half the 200 miles from Los Molinos to Mill Valley. I met them halfway, and enjoyed a happy month of reminiscences. Each evening, Aunt Susie would tell me a part of the story which I wrote in longhand. Each morning, as I went to work, she would reread, correct if necessary, and check the map and dates of each child's birth, in order to assure the accuracy of the chronology. |

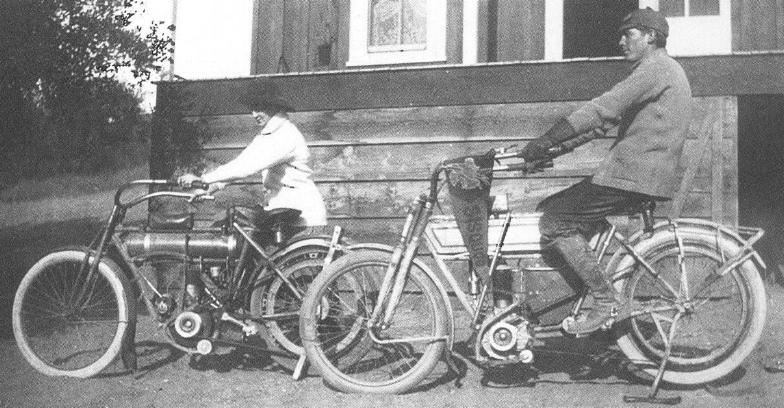

Susie Cundiff and her brother Aaron with their motorcycles in 1911

|

LEAVING MISSOURI 1899 When the trip began, Mother had prepared white bread, and foods which could be eaten easily and would keep, such as cookies and ham. These foods made it seem like a picnic for a few days. One evening Lucy set up a cry for corn bread! So hard to make! As we got out towards Rocky Ford, Colorado, we stayed awhile as Dad had to write to our home in Missouri for some money. The water was so alkaline that he had to buy water to drink. It was 10 cents a gallon. A man would work all day for 50 cents. We had 2 water buckets with us, made out of red cedar. These buckets finally gave out. One time, Dad had walked along far in front of us; we came up to him sitting on a log. He had found a small heating stove! a long square type. Perhaps some other over loaded wagon had had to abandon it. We took it with us and it warmed us all winter in Pine River, Colorado. When we left the next spring, Dad sold it for $6.00 to a family up the river about a mile. Pine River was where Louis fell in when he was a little over a year old. In the spring of 1900, our family was now six children and our parents: Charlie, me, Aaron, Lucy, Sam and Louis. Louis was born in Missouri in December 1898, and was a baby when we left there. At Greeley, Colorado, a young neighbor who had been with us since we left home, parted from us. He had wanted to 'Go West', and had been driving one of our wagons. At Greeley, he got 'cold feet' and did not want to cross the Rockies. He stayed at Greeley and became a barber. His name was Thomas Dean. |

|

1899-1900 Thomas Dean's departure meant that Dad drove the lead wagon and Mother, the one behind. Remember, Charlie was 11, I was 9, Aaron, 7, and Lucy was going on 5, all too small to drive. We went on over the mountains and going down hill, Dad would tie a big cedar tree to the back of the wagon to help hold it back. (The tree had to be cut whenever the need arose, and therefore, was a delay, as well as very hard work.) Charlie and I went on ahead to tell any other travellers that two covered wagons were coming, so that they could arrange to pass each other. The tracks or wagon roads were very narrow. Sometimes all four horses would be hitched to one wagon to pull it up a hill, then they would have to go back for the other one. This would sometimes take a whole day to move a few miles. Often, Mother would stay with the lead wagon, begin to cook and get ready to stay the night. A Spanish man and his wife, an Indian woman, and their two little boys were up in the mountains. One bitter cold morning, the two little boys were crying with the cold; the father took out a long blacksnake whip and popped it--and told the boys to "Shut up!", they did. About 10:00 o'clock one morning this family left us, turning off .on a side road to visit kinfolks. (We had all been travelling the same route and direction for several days.) We went on, on the main road after several days, we caught up with another family: a man, wife, two grown children, a man and woman. All of us travelled together until we found a place where all the menfolks could work on the railroad. We all camped together for a month or so. Their names were Thomason. |

|

1900 From the railroad camp, we went on to Bayfield, Colorado, where we all, clear down to the littlest ones, worked picking up potatoes. Mother was so surprised at the size of some of the potatoes. She weighed some that were 4 or 5 pounds each. These potatoes were put in a dugout cellar in a hillside and saved until springtime when the price would be better. We had all the potatoes we wanted to use. The other family left us at Bayfield, and Dad got a job with a rancher. Mother got a job up Pine River, taking care of a woman with a brand new baby. That is where I learned how to make sourdough biscuits on a campstove. We were to winter here at Bayfield, and the rancher told Dad where there were some old cabins that he could use as logs to build us a cabin. Dad worked for the rancher until Mother came back from taking care of the baby. Mrs. Epperson, the rancher's wife, got sick and was taken to Durango to a hospital. She was sick quite a long time, and Mother cooked at the ranch house for Mr. Epperson and his two boys. Dad and Mother got up very early each morning and went up to the Ranch house, about 200 yards, across a creek. Charlie and I and 'A' got up a little later and went up to the Ranch house for breakfast, and to get ready to go on to school about a quarter mile farther. In the spring, the melting snow made the creek rise too high for our little foot-bridge set on sawhorses. One day Louis got outside about the time the older ones were to get home from school. Lucy and Sam were out playing. Mother heard the clunk-clunk of the boards on the sawhorse bridge. She ran out, Louis, about 15 months old, was rolling down the creek, his little red dress making a bright target. Mother waded in the ice-water and pulled him out. He was blue as ink. When we got home, he was wrapped up by the heating stove, to thaw him out. Eventually, the rising water washed out our little bridge, and Dad felled a big pine tree so that is crossed the creek. We were on the stump side, and the top led acrosss towards the ranch house. To cross, Mother and Dad carried and led the three little ones, Lucy, Sam, and Louis. On the Fourth of July, we had ice-cream and had to eat it by the big stove, it was so cold outside! We were here one whole winter, spring, summer, into about October of the next year. During the summer, we could gather great buckets full of suckers (fish) and, rarely, a trout. One time that I remember, we all went trout fishing, and Mother and Mrs. McCoy fried and fried and fried and fried fish. We ate and ate until we were really full. It was dark by the time we were all ready to to go home. Our horses were pastured in a field up in the mountains, and one of the men said he saw one of our mares with a new foal -- in a few days, no foal. We guess the mountain lions got him. After this long rest, it was about October 1900, apple time in New Mexico, we started on our way again through Durango to Aztec, New Mexico. Dad freighted apples back up to Durango using two of our own horses and our wagon. A round trip was about 3 days. He made two trips like that, the second trip nearing Aztec, the wagon broke an axle. Dad was cutting a tree to repair the axle to get on home. Somehow, he fell and badly sprained his right wrist. Somehow, he got home, but that wrist caused him terrible pain. He paced and paced, finally went outside and made a big mudpack. This seemed to give him some relief. At Aztec camp, we could have all the windfall apples we wanted, so Mother dried them. Dad bought an apple-peeler that turned by hand -- one of us kids -- that peeled and cored and sliced each apple. Each apple was stuck in the apparatus by hand. Then the apples were spread out on a sheet on the sand to dry. It took about 3 days on the hot sand, in the hot sun to dry them, and then they were put in a flour sack to carry. (In those days, flour sacks were made of a very good grade of muslin.) From Aztec, we went to Farmington, New Mexico, for the rest of the winter. We had a house at the confluence of the San Juan and the Animus Rivers. Now about our 'house'. It was a building where apples were stored. There was a 'lean-to' on the side. This 'lean-to' was for our use. Our tent was hung to the side of the 'lean-to'. At one end, was a fireplace. Our beds were laid out on the floor, and our tent kept the wind out -- it wasn't a tent, but a shield from the wind. Charlie and a neighbor boy from town spent all their time digging up an Indian graveyard--old Aztec bones, they thought. About a block and a half from us lived some neighbors named Steele, a family of five children. We children all played together, as there was no school for us there. We stayed in Farmington until spring, 1901. During that time, Mother went to 'town' one day a week and worked, washing and ironing for two families. Dad worked at odd jobs. Also while here, we became acquainted with a family consisting of parents and four sons. They had a talking magpie, which we thought was fun. They bought a place in Farmington, and we said "Goodbye" when we moved on -- expecting not to see them again. When we got to Union, Oregon, about 3 years later, they had bought a lot and were building a house there! The magpie was not with them. This was the Harris Family who were destined to meet us still another time, and to go on with us to Arroyo Grande, California, in 1904. In Union, Mrs. Harris and two of the boys worked in a wool mill. But the story of Union comes later. |

|

II IN UTAH 1901 Dad walked along in front of, or beside, the wagon, always alert for possible food -- prairie dogs, fruit, berries, or squirrels; and Mother could make a feast using her little wood stove. We awoke one morning, the dog was barking furiously at a porcupine up in a tree. Dad shot the porcupine and skinned it. Mother fried it, and it was so delicious, I can remember and retaste it, even yet. The cook stove burned wood or cow chips, twisted grass, or whatever fuel was handy. The top surface was about 24 inches by 16 inches, and it stood about 16 inches high. The cooking top would hold one big kettle or skillet and the coffee pot or water-pot. The oven would hold about one big pan of biscuits. When the meal was cooked, we set the dishpan on the stove. At breakfast, the coals were poured out before we ate, so that the little stove would be cool enough to load in its place under the front seat of the wagon. In Utah, we became acquainted with some wool-haulers. There were three wagons, each with a fine team. One was a team of four horses, two had teams of six horses each. Passengers were two young ladies, a woman and her seven year old boy. The boyls mother wanted to take her son to Salt Lake City to be baptised in the Mormon faith. These passengers intended to take train to their destinations. The young women probably were hoping to find work. Wool-haulers had collected the wool and were taking it to the railroad. Two or three days before we reached the rail head, we had to ferry across a river.* (*Either the Green River or Upper Colorado River.) Just below the ferry was an old channel, too shallow and sandy for the ferry boat. We had to somehow get ourselves across this space to the ferry landing. This water was too deep and swift to be trusted. Dad put all four horses on one wagon, lashed the wagon bed securely to the running gears so that it wouldn't float away. The horses did not quite swim, but the water was way up their sides. With one wagon across, 'A', Charlie and Dad rode back across for the second wagon and the rest of the family. crossed the other channel of the river on the ferry. Everything in the lower part of the wagons was wet, so we had to camp the rest of the day, to dry out. We had completed the crossing about mid-day, and Mother cooked dinner. The wool-haulers went on, leaving their heavy wet wool to drip from the wagons. We never saw them agaln, their horses and half-dry loads were too fast for us. Another memory is of a bog of two or three hundred yards. Dad hitched all four horses to one wagon, got it across. He returned and brought the second wagon to high ground. The horses were tired and it was time to camp, as Dad always camped early so Mother could get supper in the daylight, and he could put the horses to graze, if there were any grass. This particular evening, as he walked about, he found that only a short distance up the slough, he could have crossed on dry land! |

|

III IN IDAHO 1901-2 When Little Dick Was Born Not far from Idaho Falls, Dad worked the summer in the hay, and that work ended about September. Dad was walking along behind our wagons, when a woman came out of a sturdy farmhouse and asked if he wanted to work. certainly did. This place was out of Idaho Falls on the banks of Katherine Creek. We camped there, and had to go down through the willows to the creek for all our camp water. This family gave us permission to dig all the potatoes we could use ourselves, and they supplied us with skim milk -- a gallon every day! Dad put up hay for this man, who was a teacher and couldn't do it for himself. We made a cozy camp. Little Dick was born October 2, 1901, and we moved on when he was ten days old. (This baby was christened George Edmond, but was always called Dick.) At Idaho Falls, we bought our groceries, went out and filled our water barrel. The barrel had been halfempty for 2 or 3 months, and the water leaked out down to the half-way mark, as the wood had shrunk. We camped about 3 or 4 miles out of Idaho Falls, and Dad put his mares out to graze awhile. Grass was good, so he let his saddle horse, Coolie, out, too. Coolie went out to the herd and said, "Come on girls, let's get back to that alfalfa!" So they ran away. It was 4 or 5 miles before Dad and the boys could catch those horses. It was 10 o'clock AM before they got back to the wagons. This made a very late start. We had a 60 mile desert to cross and only half a barrel of water! It was fun, we kids never had to wash at all. We drove all that day, the horses getting only a bucket of water, camped late, drove all the second day, and the third day. We saw a grove of cottonwoods far away. We drove on and on, late, late, about 10 o'clock at night, we came up against a new barbed wire fence. Dad couldn't tell which way to go in the dark, so he unhitched the tired horses and tied them to the wagon wheels. In the morning, there was still no sign of water, but we followed a wagon track beside the fence. We came at last to Little Lost River. It comes out of the hills and simply stops in a big pond. But such good mountain water! The dry, exhausted horses needed a rest. It was just after daylight, but we stopped and camped for the remainder of the day. The rancher let Dad put the horses to pasture. We filled and refilled the water barrel, so it would swell the wood and tighten. The next day we went on to Big Lost River. It wasn't lost yet! We crossed the river and camped beside it. Mother had just started supper, when Dick started crying and crying. Nothing would stop him, not her medicine, not anything, so she told me to finish the supper. "I will take Dick to bed." Magically, Dick stopped crying. He had been travelling since he was ten days old, was simply exhausted. He slept and slept. A few days farther on, Dad got a job where the railroad was going over the mountains. This was cold, cold country. All the people who had lived there told Dad that he must get out before winter, as he would have to buy feed for his animals all winter. We still had our dog, Old Spot, white with big black spots on him. We left after Dad worked a little over a week, arriving to within 20 miles of Boise, where Dad got another job hauling dirt up to fill a dam that had been washed out. There was still some water behind the dam and that froze so solidly that people came to skate there in the winter. We were camped--living in a tent there all winter long--a tiny baby, parents and six other youngsters. Our only warmth was the little cookstove! yet, I don't remember any misery from the cold. Brother Charlie was 'flunky' at the cookhouse, for the men who worked on the dam. Mother and 'A' had to hitch up the team and drive about a mile to get good clean water when we needed it for cooking and drinking. Our camp was near a fairly new cabin, unoccupied, for a man had been killed in that yard. We sometimes went in that yard and looked about, as youngsters will. For Thanksgiving and Christmas, the 'cooks' at the cookshack wanted Mother to come up and cook the turkey. .She did -- turkey and all the dressings. We got the scraps and leftovers. This was the first time I ever saw macaroni. The cooks made soup with macaroni, then Charlie brought whatever was leftover home for us. There were so many teams working on that dam, I can't remember how many. In March, we had a blizzard that was so fierce, the cold was so intense, and snow six or eight inches deep so that horses' hooves would get seven or eight inches taller(!) with the ice buildup. When we got up in the morning, the snow was all over our tent, wind from the north. It was so cold that Dad couldn't build a fire in the cookstove. He tried until nearly noon, finally piled the kindling and wood on the floor, a dirt floor, remember, and managed to make a fire there. Mother got up, cooked a little mush, we ate, and went back to bed for almost the rest of the day. After that March storm, we went into Idaho Falls to camp, as it was still too early to start on the road. We camped by a big irrigation canal that came out of the river there. Dad would work all week, six days, and would chop wood all day Sundays. We kids would carry it to camp, where Dad could finish trimming and cutting to stove size. Dad's job at that time was clearing sage brush from about ten acres that the owner planned to irrigate and farm. There was quite a group of people camped there waiting to move on. The campground was within sight of the city dump -- just across the river from us. The children in the camp had dolls and dolls and dolls which the merchants dumped after Christmas! Some were the 'kid' body with bisque heads. The other children divided and shared the dolls with us. From Idaho Falls on the Snake River, we went on to Union, Oregon. On the way, Dad found various jobs. This was 1902, mid year. |

|

IV UNION, OREGON 1902-3 After Idaho Falls, our next stop for any length of time was Union, Oregon, in the northeast corner of the state. We stayed there one winter and half the summer. In the spring, everybody big enough thinned sugar beets. Charlie and Dad chopped them out with the hoes and Aaron and I crawled along the rows pulling out all except one plant in each bunch. In one field each row was one-half mile long, and all we could do in half a day was two rows. When the beets were finished, we moved about 200 miles farther west to Myrtle Point. Myrtle Point was still about a day and a half from the ocean. One day Dad was walking along in front of the wagon, as he usually did, he asked some little boys playing by the road, "How far is it to the frog-pond?" They found this very funny! Elsie was born at Myrtle Point, Oregon, on March 29, 1903. When we reached the beach at Bandon, there was a big whale washed up on the beach. We smelled him before we saw him. Also here, Mother found a square whiskey bottle. She filled it with ocean water and we took it back to Myrtle Point with us. In a few days, there was a terrible odor--we wondered if someone had brought back some of the whale! It was only the bottle of ocean water. The next year in July, 1904, we loaded up the wagons and went up the hill. The horses hadn't worked hard for about a year and half, so they had to be hitched double to get up the first steep hill. We got out to the mail box, about a mile and a half from our starting point, where we camped the night. Next day, we went 12 or 15 more miles to Myrtle Point for the night. We got our supplies and continued on another 12 or 15 miles on the Kitchen Creek road. We could look right back over the canyon and see where we started from two days before. It was Lucy's and Aaron's job to drive the cow and her yearling calf. We could only go. as far and as fast as those sets of legs could go. At every camp, every child big enough would get their tin cups and gather salmon berries and blackberries. Mother would milk the cow, so we could have cream on our berries. Charlie drove one wagon, and Mother drove the other. I had to ride with Charlie so I could put on the brake whenever we needed it. Mother had the tiny kids, and had to do her own 'braking'. On a bad hill, Dad would get in her wagon and 'brake' her wagon. * (*A wagon brake is a hard pressure on the wheels applied by pulling a lever in the wagon. On a steep hill, the brake had to be applied to keep the wagon from running into the horses, as they were going down hill.) Charlie was now 16, I was 14, Aaron was 11 1/2, Lucy, 8, going on 9, Sam was 7, Louis was 5, Dick nearly 3, Elsie was just over a year old, and able to walk. Each evening, as soon as Dad and the boys got the tent up, I had to make down all the beds while Mother cooked supper. Each morning, I would fold the beds while Mother got breakfast. Elsie had a little red dress, she says she never remembers owning a red dress--that may have been her only red dress,--but it made it easier to keep track of her. We were three or four days getting to Port Orford, and went out to see a rock where a ship had gone aground years before. The Indians had attacked the ship and had killed some of the people. After night, others had managed to get up the coast and get away.* *(On Hwy. 101, Port Orford is about 70 miles north of the California line.) It took us days and days of travel to reach Healdsburg, California about 300 miles as the crow flies, but much more over ruts and tracks of the wagon trail. This is now the route of Highway 101. It is along the coast for part of the way, then comes inland between two ranges of mountains. At Healdsburg, we camped between the road and railroad tracks, as a train very seldom ran at night. Dad and the boys hoped to get work here. There was a bunch of Indians who had got some wine, and were having a great time, so they camped on the tracks. One woman settled down between the rails, and a woman and man were right beside the tracks and their dogs were all around. That night, a special train carrying the presidential candidate, Theodore Roosevelt, came through which minced the squaw and a few of the dogs. We camped there several days, working and picking white grapes, then moved a bit farther into the country to pick more grapes. During this time, we became acquainted with another family, the Howes, a Mexican man, American woman and their two children, Tracie and Robbie, 7 or 8 years old. This family travelled down the coast with us. At Healdsburg, Dad went into the feed store to get some grain for the horses. The feed store man had some dried fish which he sold to Dad for a fair prlce. We ate dried fish and grapes and loved 'em! for a week or two. Dad had bought about half a barley-sackful. They were little smelt. On down the valley, we got jobs picking hops, clear down to the smallest ones of the family. Hops are very light weight, it seemed to take hours to fill one of the long sacks, about the size of a cot mattress. |

|

V CALIFORNIA 1904 The cow and calf didn't have grass to eat, couldn't eat grain alone, and were trying to eat the willow leaves. A cow's milk is flavored by all that she eats, so we had to buy some hay. At Petaluma the chicken feathers everywhere made it look like snow. Petaluma was called the egg capital of the world at that time. (In 1970's, it is the wristwrestling capital!) The Howe family, man, wife and two children joined us somewhere in this area, and made our caravan total four wagons as we were also joined by a lone man, a widower. The Howe family separated from us after we left San Francisco, but Ed Rears went all the way and became a valued friend. We crossed the Bay by ferry at Sausalito; Lucy remembered the sculptured cement elephants at Sausalito always. Lucy often mentioned remembering passing a shell mound, but we don't know just where that was. Below: Lucy Cundiff, my grandmother, in 1904

At San Francisco, we were quite a sight, creating a sensation with all our wagons, horses, two cows, children and two dogs. School was just out for the day; children followed us for blocks, shouting, "Circus! Circus!" The cow, calf and colt were tied to the wagons, being led, so that all the children of the group could ride in the wagons. We were hours going along old cobblestoned Mission Street, getting to a place where we could camp. The Howe's wagon broke an axle, and we all laid over a day until it could be fixed. Somewhere before Pismo Beach, we parted with them. Ed Rears stayed with us. At Ocean Beach we bought some provisions and went out of town to stay for several days. Ed Rears thought he saw a watermelon patch -- he liberated a melon. When he cut it, it was pie melon or citron! We ate clams for several days at Oceano Beach -- but I am ahead of my story. On the way south from San Francisco, we started to the San Joaquin Valley for summer work. We met our old friends, the Harrises from New Mexico, and Oregon, coming out of the valley. They told us there was no work in that vicinity or direction. We all turned southward. The Harrises, there were six of them -- four boys and the parents -- had two wagons, and they joined us. Having lost the Howes, we were now five wagons in our caravan. We continued together as far as Arroyo Grande. The Harrises bought an old secondhand creamery, took it apart and built a nice home on a little piece of property they bought. We settled there too. The Harris boys 'worked out'; Dad and Ed Rears got a job sawing cord wood for the oil wells being drilled for tests. We rented a piece of land, cleared it, and sold the wood, cookstove size for $4.00 a cord. Harrises wanted a bigger place and could not quite afford it, so they talked Dad into buying half of it. That was our place in Arroyo Grande. Mary was born in Lopez Canyon near Arroyo Grande, on February 1, 1905. We lived in Lopez Canyon about 2 years. It was here that we met the Rhyne families. Hazel was born April 27, 1907, while we were still in Lopez Canyon. It was here also, that Lucy fell while playing at San Manuel school. The injury didn't seem too bad. The kids were playing 'horse' and running around the school yard, hard-packed dlrt, wlth hobbles on. She dldn't even skln her knee, but it stayed more and more sore and swelled until it looked as if it would burst if touched. Mother moved Lucy, Mary the baby, and herself down near Arroyo Grande so the doctor could see Lucy twice a day. Dad hauled wood down to Arroyo Grande and sold it to buy groceries. He also hauled wood to the Parkersons' to pay for keeping Mother, Lucy and Mary. They were there about a month and a half. The Parkersons traded Dad some old lumber so that he built a cabin about 12x14 feet, up in Lopez Canyon. He hung the tent over one end to make a place for the boys to sleep. Dad split shakes out of cottonwood trees to make the roof for that little house. From here we went to another canyon and rented a house with a piece of hill land. These people were named Hasbrook. We picked grapes for them each fall. They had a post-office stop at their place and a small winery. Wildcats would come down from the hills and get our chickens. Our good old dog, Sport, was so good to watch the chickens and tree wildcats. I killed two wildcats he treed for me. The first one I shot at, I was uslng Ed Rears' gun; it was too easy on the trigger and I only shot the cat's foot; he fell down. The dog treed him again and I shot him again and got him. I took a picture of Sam and Louis holding up the cat. While we were at Hasbrooks', our cow which we had driven from Oregon, got the Black-leg and died. (Blackleg is an infectious disease of cattle and sheep, usually resulting in death. However, there is now a very effective vaccine to protect against it.) From the Hasbrook place, we bought the place near Arroyo Grande. We all attended the San Manuel School, about 2 miles from our Lopez Canyon place. One fall when I was in fourth or fifth grade, we had a bean crop. The boys and Dad were working to get in the crop. I quit school to help get in the beans, and that was the last formal schooling I ever got. I was about 10 years old. Lucy, Elsie, Sam and Louis all went to our Arroyo Grande school. Lucy rode a horse to school; she was injured at about age nine. It was about 1908 when we moved to Arroyo Grande to live. Mary was a toddler. We lived there about three years. Dad raised hay to sell, and vegetables for ourselves. We had bought a Holstein heifer with her first calf from Steve Rhyne While we were in Lopez Canyon. She was the meanest cow, determimed to go home again, I guess. For about once a month, she would crawl through a barbed wire fence and split her teats, then she would be a fury to milk. We used to pick strawberries for market for the Rhynes. The Harrises also had strawberries for market, and I picked there, too. These were three pretty good, settled years, except for Lucy"s pain and crippling. Hazel was a baby, and a little boy was born May 11, 1910. He was born dead. |

|

VI THE FLOOD 1911 The rains began--raining unceasingly for days, this was February and March, 1911. Several neighbors, about a year before, all went together and built a bridge about 150 yards above our house over the all-year Lopez Creek, which passed about 50 or 60 feet from the house. We had two sheds filled with hay, tools, corn, popcorn, etc., and wagons near them, above the house. These were on the creek bank. It was still raining, and we took the younger children, Elsie, Lucy, Mary and Hazel, over to the Parrishes one mornlng. Mother and I stayed at the house until after the midday dinner when Dad came home, and told us to load some of our best clothes and the like, in the wagon, so he could take them down to Ben Stewart's barn, about 150 feet feet farther from the creek. We put some things in the barn and were going to take changes of clothes over to the little ones. We were about 100 feet from the house, Mason's two cows broke loose, and Mr. Mason told us to wait until he could get his cows. One man had a wagon with only one horse, and he kept going. He just barely got in front, (ahead) of the water. We stopped to wait for Glenn Mason, the flood waters struck and took the two horses right off the wagon and down through two barbed wire fences. That was the last we saw of them and they were a neighbor's horses. Mother and I were on that wagon and we got off and got back into the shallower water. The wagon didn't go just then, but it tipped over and spilled all our possessions, our phonograph, clothes, treasures, all--all gone, wagon and all. Sam, Louis and Aaron were walking in front of the wagon, they were able to hang onto a telephone pole; climbing up as the waters rose. This was occurring just at dusk. The pole was near Ben Stewart's barn -- but the barn didn't go. Our sheds went, our tools, too; Dad and the boys had spent the day moving things back -- they had moved the spare wagons back far enough - -we didn't lose them. Mother and I kept walking in knee deep water -- our long wet dresses made it very hard to stand up. Shorty came back to see if he could help us. I said, "No, help the boys," as they were in far deeper water. He started to swim towards the bank, his fingertips were almost touching -- and he was swept away. Dad and some of the neighbors had got a rope to throw out to where the boys were. They threw the rope out, fastened Louis and brought him in. The wet rope was too heavy, they could never throw it out that far again. Suddenly, the pole sheared off at the bottom, and it swung suddenly towards the bank, held by the wires at the top. Aaron was able to get on the bank. Sam may have been hit by the pole, or the fall jolted him loose -- he was swept away. It was dark now. At about the same time as the pole fell, the debris, trees, trash, etc., piled against the little bridge broke the bridge. The waters swept back into their proper channels. Dad and the other man were able to get over to Parrishes, to return with a lantern for us. We didn't know Sam was gone until we got to the Parrishes. Dad knew. He had seen him go. They were still trying to throw the rope when the pole broke. We stayed at Parrishes for two or three days until we could dry out and arrange to move back to our house. The next day Sam's body was found washed up across a road in an old header barge, about a mile and half below town, about three miles from our house. Shorty's body has never been found. He was an Englishman, named William Brampton. Dad tried, but had no clue as to any family to be notified. *( A header barge is a big flat rack with built-up sides that can be put on a wagon body to haul grain or hay.) That terrible night as we waded and waited, I had found a big salmon, as we continued wading and waiting, I had thrown him into our house. Next morning when we went home to assess the damage, an old skinny black cat that we had, had eaten her fill! We hadn't been able to find the cat as we were leaving the day before. There was no floodwater inside our house which was raised from ground level about three steps, but the creek bank had washed away to within a yard of our back steps!

Sam Luther Cundiff, born in Missouri, December 8, 1896, drowned on March 7, 1911, was buried in the little cemetery in Arroyo Grande, Calif. |

|

Nothing was known of Shorty Brampton's family, or his relatives, if any, and nothing could be done about notifying his English roots. Charlie had a job in the oil felds at Sisquoc at the time of the flood. His home was a little house on Dad's place. While he was working away, Loie and their two little girls, Ethel, 3 years and Thelma, almost a year old, had gone back to Lopez Canyon to her father's place. They were all up there when the flood waters tore out the bridge and washed away their own little house. This flood disaster destroyed all their possessions, though the house was unoccupied at the time. Charlie's now homeless hamily went with him when he returned to work at Sisquoc. Not long after the family settled in Arroyo Grande, Charlie and Loie Burns had eloped to Lodi, without benefit of clergy. Dad had given Charlie a bay mare named Monday. who had travelled with us, or pulled us all the way from Missouri! He was to work in the grapes; we put Loie on the train to join him -- she was almost 18. When her father, Mr. Burns, found out they had neglected to be married, he had had Charlie put in jail in San Luis Obispo. Their little girl, Ethel, was born September 9, 1908. (They were married.) I don't know what happened to Monday. Charlie was not good with horses, but Loie was a wizard. She could handle them expertly. |

Continue to Page 2 of the Cundiff Saga