Internet Astrophysics Celebs Carroll & Gay to Speak in Second Life

Posted on February 4th, 2010 — permalink

For those of you who haven’t been following my blog or watching my twitter or facebook updates, you may not realize that there are regular public-outreach astronomy talks in Second Life. These are designed for the general public, and are open to anybody. Indeed, because a Second Life account is free, they really are open to anybody. These talks are on Saturdays at 10 AM pacific time / 1 PM eastern time, are sponsored by the Meta-Institute of Computational Astrophysics, and are held in MICA Large Amphitheater of the StellaNova region in Second Life.

This series has historically been called “Dr. Knop Talks Astronomy”, because through the end of 2009 I have given the lion’s share of the talks. Indeed, I was thinking about it the other day. The last semester before I left Vanderbilt, I was contacted by the people who make the CD series called “The Great Courses”. These are CDs with lectures from university professors on their topics of expertise. Based on some podcasts of mine that were online from several years ago, they contacted me and asked me to come audition. The idea was that if I passed it, they might well produce a course from me. However, when I left Vanderbilt, and could no longer call myself a “Professor of Physics and Astronomy”, they were no longer interested in me.

It occurs to me that given the number of talks I’ve presented so far, those who have come to most or all of my talks have effective received the equivalent of one of these CD series on “hot topics in astronomy.” Indeed, it was more than that, for not only were there visuals (i.e. my slides), but it was interactive. You could ask questions, and also discuss the talk with the others present.

If you look at our schedule for this coming semester, you’ll see that we’re starting to mix things up some more. I’m still giving more of the talks than any other single person, but we’ve got a larger range of guest speakers. You can see who’s coming up soon by looking at the Upcoming Public Events page.

Last week, we had Nobel Prize winner John Mather speaking about the history of the whole Universe, and of hopes and plans for the upcoming Webb Space Telescope. In the next two weeks, we’ll have two “Internet Celebrities” talking. Sean Carroll, one of the authors of the popular physics blog Cosmic Variance, will be talking about his recently released book on the nature of time, From Eternity to Here. Then, Pamela Gay, host of 365 Days of Astronomy and a member of Astronomy Cast, will be speaking in two weeks.

Drop by and hear us. These talks can be very good… and, while you shouldn’t believe me if I tell you my own talks are good, others have told me that they are. The immersive environment of virtual worlds means that you really feel you are there— John Mather was commenting on this just last week after giving his talk.

Comments Off

Posted in Physics & Astronomy, Science, Second Life, Second Life Events |

Me in the Infrared

Posted on January 5th, 2010 — permalink

The Spitzer booth at the AAS has an infrared camera set up, so you can see what you look like in wavelengths just longward of one micron.

This is me:

I’ve got my mouth wide open in a jolly smile, which is why that part is glowing. Meanwhile, you can see that my glasses do not transmit infrared light as well as they transmit optical light, and are not as warm as my face, so they show up as dark spots.

1 Comment

Posted in Physics & Astronomy, Science |

How long does it take planets to form?

Posted on January 5th, 2010 — permalink

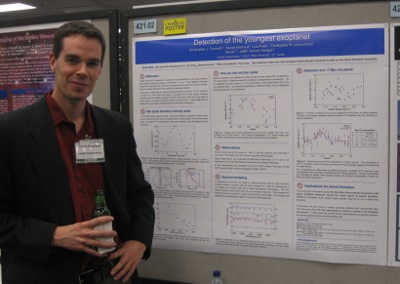

One thing that’s currently unknown— and there remain debates among the theorists and modellers— is how long it takes for planets to form. Timescales vary between 1 and 10 million years. What’s more, based on our understanding of the environments around very young stars, big gas giant planets have to form a fair distance away from the star (equivalent to where you find Jupiter and Saturn in our Solar System), yet we’ve found lots of Jupiter-sized planets very close to their star… so, our current understanding is that those planets not only have to form, but have to migrate in.

One thing that would help us figure out the timescale for planet formation is doing searches for planets around very young stars. Below is a poster that reports the discovery of the youngest exoplanet known:

Shown is graduate student Chris Crockett of Lowell Observatory. (And, if his advisor is looking at this, no, that’s not a beer!.) (Although, to be perfectly honest, I have to admit that the reason I sought out this particular poster is that the second author is Naved Mahmud, graduate student at Rice who worked with me at Vanderbilt, and who made one of the nicest comments a blogger could ever hope to get, so, see, flattery sometimes does get you somewhere!)

What they’ve discovered is a planet orbiting a Classical T-Tauri star. If you don’t know what that means, you’re like me… or, rather, you’re like me several years ago. However, I was at Vanderbilt for six years, where David Weintraub and his students were doing a lot of work on T-Tauri stars, so as a result I learned something about them. T-Tauri stars are stars like the Sun, only still in the late states of formation. They’re not protostars, really, any more, but they haven’t yet ignited fusion at their cores. They are what’s known as “Pre-Main Sequence” stars. (Yes, folks, that’s what astronomers think PMS means.) There are “Classical” and “Weak” T-Tauri stars, based on the strength of the Hα emission line. Our understanding is that the Hα results from accretion of gas on to the star— and Crockett et al. have more evidence to support this. What does this mean? There is still a substantial gas disk around the star, putting the protoplanetary disk almost certainly within the first million or two years of it’s life.

In other words: what these guys have discovered is a Jupiterish planetary mass condensed around a star that’s at most a couple of million years old. This is an extremely relevant constraint on how long it takes to form planets, and will be big news for those who try to theoretically understand the original formation of our Solar System and other planetary systems.

This work should be submitted to a journal sometime soon, and presumably sometime thereafter it will show up on arxiv.org.

Comments Off

Posted in Physics & Astronomy, Science |

Result from Kepler : a planet’s light blocked by a star

Posted on January 4th, 2010 — permalink

This morning the invited talk at the AAS meeting was William Bourucki of NASA/Ames talking about first results from the Kepler mission. The coolest thing he described was an object that’s too hot to be a planet, but too big to be the kind of star it could be…! More about that later.

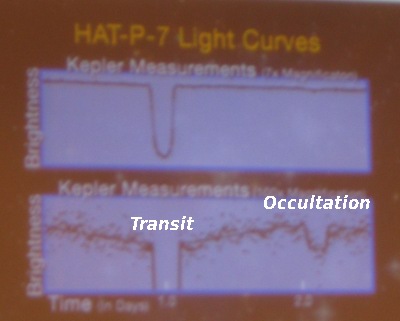

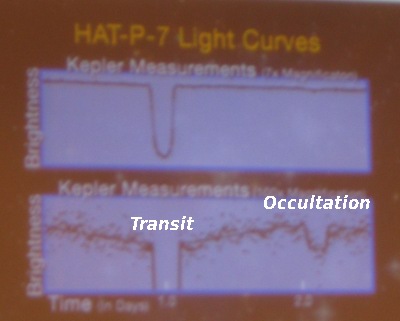

Right now, I want to show my blurry snapshot of his plot of the lightcurve of an already-known exoplanet named HAT-P-7:

This is a plot of the brightness of the star versus time. This was a previously known planet. In the top, you see the Kepler data that results from when the planet transits the star. That is, the planet moves across the face of the star, blocking out a little bit of the starlight, causing the star to get just a wee bit dimmer. The planet is much dimmer than the star, so it only blocks out a bit of the starlight, but Kepler is sensitive enough that this is an extremely strong detection.

What’s cool is when you zoom in on the plot. You see a second dip to the right. What you’re seeing there is the light of the planet being blocked by the star. The planet shows reflected light from the star, which adds to the overall light you see. However, when the planet is occulted by the star, you no longer see that reflected light… and you get a secondary dip.

A number of extrasolar planets have been detected by looking for stars whose light is briefly blocked out due to an orbiting planet moving in front of the star. Kepler is a spacecraft designed to find lots of these planets. It’s really cool that it’s sensitive enough that it’s seeing the light of a planet blocked out by a star…!

Comments Off

Posted in Physics & Astronomy, Science |

AAS Astronomy Events Live Streamed into Second Life

Posted on January 4th, 2010 — permalink

I’m at the annual big meeting of the American Astronomical Society this week in Washington, DC. Lots of stuff going on, and I’m already overwhelmed by the sheer number of people here. (And, also, depressed by the number of young people here in comparison to the number of entries on this list.

Several of the bigger events— press conferences, invited talks— are going to be live streamed into Second Life. Drop by the Astronomy 2009 island to hear the talks, including the Wednesday at 8AM Eastern / 5AM Pacific talk by astronaut and Hubble Mechanic John Grunsfeld. These events are hosted by Astronomy 2009 and by the Astrosphere New Media (Pamela Gay’s and others’ new venture). A full schedule is here.

Remember that a Second Life account is free! Drop by and check it out. And, once you’ve got a Second Life account, nothing will be stopping you from coming to hear my public astronomy talks that I frequently give.

1 Comment

Posted in Physics & Astronomy, Science, Second Life, Second Life Events |

I’ll be joining the faculty of Quest University in Fall 2010

Posted on December 21st, 2009 — permalink

Last week, I flew out to Squamish, BC to interview for a faculty position at Quest University. Two days after I returned, they called me to offer me the job, and I accepted it. Next summer (July 2010), Alyson and I will be moving to Squamish, and starting next Fall, I’ll be a Tutor of Physics at Quest. As far as I can tell, this is my dream job.

Although there have been moments where I questioned this, I have long considered it my calling to teach at the college level at a small liberal arts college. Eight years ago, when the only offer I had was at a large research University, I thought I could make that work— and I almost did. Two and a half years ago, after the quashing of the notion that I could stay forever at a research University, I thought I was never going to be able to work at my true calling, and I took up a (enjoyable and rewarding) backup plan. Half a year ago, when booted out of my backup plan, I despaired that I would ever be able to do anything but “just make money”.

So why do I think Quest is my dream job? I sent out applications to 14 small colleges, 13 of which were in the US, a couple of months ago. I didn’t apply to large research universities at all this time around. However, I’m in that awkward position of being somebody who’s 13 years past his PhD and not a superstar. It’s hard for colleges to hire somebody like me because they have to figure out if they should evaluate me for tenure straightaway, and, crucially, because there is a tremendous oversupply of extremely capable and extremely well-resumed young physics PhDs out there that they can hire for less money. The competition is stiff, and since my realistic and non-superstar resume was competing with extrapolations from very high-end post-docs, I knew it was a long shot. However, even at the beginning, I could tell that Quest was a different sort of place from even most of the small liberal arts colleges. And, I believe it was some of those differences that both made the place so attractive to me and made me “hireable”.

The two single most important things about Quest are this. First, it’s a small liberal arts undergraduate college (enrollment currently in the 200’s, with a target of 600 to 800 in the next five years). (It turns out that while small, secular, independent liberal arts colleges are all over the place in the USA, Quest is unique in Canada.) Second, it’s a new college. Indeed, it’s only had students for three years, so nobody has graduated from there yet! What’s more, not only is it new and thus free of the notion that “we’ve always done things this way here”, but it was also deliberately founded with the best modern understanding of what really makes for a great undergraduate education.

Like Colorado College, Quest operates on the block plan. Students take only one class at a time, and they completely focus on it for three and a half weeks. I don’t have much direct experience with this myself (the closest I’ve been is teaching introductory astronomy over the course of five weeks at Vanderbilt during the Summer term), but I have talked to a number of people who find that they like this model of coursework far better than the traditional “scattered attention over a semester” model. And, given my own tendency to get into something and to want to hyperfocus on it, it appeals to me.

When I was sending out applications, I had to edit my “statement of teaching philosophy” a bit. Originally, I had a statement to the effect of “modern physics educational research has shown that straight lecturing is not an effective way to teach physics courses”. I realized that that statement might directly offend people on the committees that would be reading my applications, and stated it more cagily. (”Much recent research into physics and astronomy education has shown that the most effective use of class time comes when students actively engage the material.”) Quest, however, contained more or less the same original statement in their job advertisement. This was clearly a place that “gets it”. When I visited Quest, I was quite impressed. The faculty members I met with were dynamic and intelligent, and truly cared about undergraduate education as their primary creative endeavor. They were high on the institution, and they were high on their students. Indeed, I was also impressed with the students I met, both in the “sample class” I taught, and when I chatted with a few of them and some others afterwards during lunch. I would say that I was even more impressed by these students as a group than I was by the students at Pomona I met with when I applied there several years ago— previously, that was the group of students I’d met during job interviews who impressed me the most. (Of course, the most impressive undergraduate students I’ve worked with over the years include Jessica Hodges, James Schlaerth, Naved Mahmud, Jonathan Stricker, Andrew Collazzi, Anders Jensen, and Cameron Pittman… i.e. the ones who’ve done research with me!) (When I interviewed at Vanderbilt nine years ago, I met some graduate students, but I didn’t teach a “sample class”, nor did I meet any undergraduates.)

Quest also doesn’t do tenure. Many would view this as a disadvantage. And, indeed, I can fully appreciate the value of the perk of having a permanent assured job. But, I’ve been on the other end of tenure, and anybody who read my blog a few years ago knows that I suffered greatly because of it. A friend of mine once said that she didn’t know anybody who went through the tenure process without having it f–k them up severely. While many point to the “deadwood” problem as the “flaw” of tenure, David Helfand (the current president of Quest) said what I also think— that that problem is overblown, and is only something like a 10% effect. The real problems of tenure is that it limits academic freedom for pre-tenure people. I don’t know that that is such a severe problem in the sciences, but you can easily imagine how in any department the young, bright, and dynamic faculty may have to constantly censor themselves to avoid torquing off a powerful ego in their department. Heaven knows that I didn’t manage keep my mouth shut, and freely offended several senior professors in my department… and I still believe that had I received an NSF grant, I would have had no problem getting tenure at Vanderbilt, because there were enough other senior professors who agreed with the things I was saying. However, tenure did put tremendous stress and pressure on me, and that stress and despair undermined my research productivity my last few years at Vanderbilt. All in all, by the end, for me, the tenure system had nothing but negative effects while I was at Vanderbilt. As long as Quest does real faculty evaluations that really evaluate whether they are doing what they’re supposed to be doing well (and I believe that it will do this), I’m just as happy to be shut of the whole tenure system.

Indeed, I suspect the lack of tenure made it much easier for Quest to consider me than it would have for other colleges. They didn’t have to look at somebody 13 years out from his PhD with six years experience teaching at the University level and think about tenure clocks or any of that. I’m just one more contracted Tutor. (Oh, and, they call them Tutors there in order to emphasize that our role is not to “profess”, but to enable and aid the students in learning how to think and how to learn.)

A lot of colleges and Universities include a “writing across the curriculum” initiative. When I learned during my final interview that Quest is trying to start a “quantitative reasoning across the curriculum” initiative in addition to this, I almost fell over under the “this must be too good to be true” response. I’ve long bemoaned that Universities understand the value of writing while missing the equally important value of quantitative reasoning.

Because Quest is not only a new University, but a small University where faculty have no choice but to teach some courses outside of the “straight and narrow” of their fields, I am very sure I’ll be able not only to challenge myself by teaching some of their Foundation classes, but that I’ll be able to create new and interesting courses that might transcend what you’d fine at a “normal” Physics department. I’m not just thinking about an undergraduate fluid mechanics course (which one student at lunch asked for while I was visiting), but I may one day before long get to teach a class about the science found in Tom Stoppard’s plays…. It’s all opportunity, it’s all exciting future.

When I left Quest this last week, I felt that this was the place where I was supposed to be. It almost made me think that perhaps there was some Plan at work, that I taught at a research University for six years not because I went where I had the offer (instead of to the sort of place I thought I really wanted to teach), but because it was preparing me while Quest University was in the process of being created. (I don’t really believe that; if you are lucky, it’s not a mystical force, but it’s merely because, in the words of Spock, “random chance seems to have operated in [your] favor”.) I was very excited when they called me on the phone to offer me the job, and the only reason I didn’t accept it on the spot was that my wife was napping, and I did want to check in with her before accepting a job that was going to include a move to western Canada.

I still don’t know everything I’m going to be doing during the first half of 2010, but next Summer I’ll be moving to Squamish, and next fall I’ll be a Tutor in Physics at Quest University.

29 Comments

Posted in Personal Updates, Physics & Astronomy, Science |

“Dr. Knop Talks Astronomy” — archived on the web

Posted on December 15th, 2009 — permalink

I give regular talks in a series entitled “Dr. Knop Talks Astronomy” as part of MICA’s public events. These talks are in Second Life, so people from all over the place can come to them.

I give regular talks in a series entitled “Dr. Knop Talks Astronomy” as part of MICA’s public events. These talks are in Second Life, so people from all over the place can come to them.

if you’ve missed them, and want to catch up on them, at the site above slides from most of my talks are archived, as well as MP3 files of the audio in many cases. However, there are now three of the talks online that have been recorded fully in video. Of course, it’s not the same as being there, since you can’t ask questions and interact, but it might give you a sense of what goes on at these things.

The first one is a talk about how we know that Dark Matter exists that I gave several months ago; this talk is online at PookyMedia.

More recently, Geo Meek has recorded my most two recent talks, and there is now a Dr. Knop Talks Astronomy channel at livestream. The two talks online there are one all about redshift (the Doppler shift, gravitational redshift, cosmological redshift), and my talk a few days ago about black hole misconceptions. Special thanks to Spike McPhee (aka Paradox Olbers) for supporting this latter effort!

Joe Bob Says Check It Out!

(Update: it looks like the black hole talk is not online at livestream yet, as of 2009-12-15 13:40. However, I believe it will be before too long.)

Comments Off

Posted in Cosmology, Physics & Astronomy, Science, Second Life, Second Life Events |

The Moon in “Heroes” is VERY different from our Moon.

Posted on October 25th, 2009 — permalink

My wife and I tend to watch TV shows a year after they come out; we rent the DVDs from Netflix and watch them then. We’re right now working our way through the third seasons of Heroes. If you’ve watched even the first season of Heroes, you know that Eclipses are a Big Deal and somehow cause or affect superpowers in humans. Well, there’s another total solar eclipse coming in Season 3. Here’s a screenshot (also showing a vapor ring left behind as Nathan Patrelli took off flying at high speed) of the moon about to eclipse the Sun:

OK, first, the good. Yes, the Moon is apparently about the same size as the Sun in the sky. (Yeah, the Sun looks a little bigger, but that’s probably because of the glare. There’s about to be a total eclipse, so they’ve got to have about the same apparent size. In any event, the size is close.)

Now, the bad. When the moon is that close to the Sun in the sky, it is a tiny, tiny, tiny, very thin crescent, basically a new moon. You will not see it at all, until it starts to actively block out the Sun. The reason for this is that since they’re so close to each other in a sky, it’s almost a straight line from the Earth to the Moon to the Sun. The distance to the Moon is much less, so the Moon is between us and the Sun. Thus, the side lit up by the Sun is the far side of the Moon from us.

Yet, here, instead of an almost-new moon, we see an almost-half-full moon! For half of the moon to be lit by the Sun when we see the two right next to each other in the sky, the moon would have to be at about the same distance from us as the Sun…. Well, it’s not quite half, so it’s a little closer, but we’re talking inside the orbit of Mercury here. And, for the Moon to look as big as as the Sun when it’s that far away, it will have to be physically almost as big as the Sun!

In our Universe, the Moon is a satellite of the Earth, about 1/4 the diameter of the Earth, and orbiting the Earth. The Sun is about 100 times the diameter of the Earth. The reason they look about the same size in the sky is because the Moon is so much closer.

From the evidence in the image above, however, the Earth of the Heroes Universe is very, very strange. They orbit a binary “star” system, including the Sun and the Moon… although the Moon is not a satellite of the Earth at all, but a binary partner to the Sun. However, the Heroes Universe Moon is an extremely bizarre object, for despite being so large, it does not shed any light of its own in the optical. It’s clearly not a large gas cloud, for you can see by looking at it that it’s a solid object with “seas” and craters and all of that. So, it’s something that has somehow managed to be as big as the Sun without triggering fusion inside to make it glow.

Wow.

Well, given that all these superpowers work, we already knew they were operating under different laws of Physics, so I guess we shouldn’t be surprised.

My only fear is that people watching the show don’t realize that the producers are being very clever here in showing us that the Moon is a gigantic object that is nearly as far away as the Sun, very different from the case in our own world. I fear that some people watching might either think that the producers of the show have done the typical Hollywood thing and made a boner of a mistake, or may think that it’s entirely reasonable to see a near-half Moon right next to the Sun in the sky. I hope in upcoming episodes there will be dialog between the characters that more clearly reveals the nature of their Moon as a star-sized object close to the Sun.

Comments Off

Posted in Physics & Astronomy, Science, science & society, science fiction |

Astronomy talk in Second Life : Solving the 3-Body Problem

Posted on September 18th, 2009 — permalink

I’ll be giving a talk in Second Life on Saturday at 10AM SLT (Noon CDT, 17:00 UT). This is part of the regular series Dr. Knop Talks Astronomy.

Double and Triple Stars: Solving the 3-Body Problem

If you look at the stars in the night sky, you discover that a very large fraction of them are not isolated, but are in fact in binary star systems, or even in larger groups. Using Newton’s gravity, we are able to perfectly solve for the orbits of a system involving just two bodies, but it’s impossible to analytically solve it for more. In this talk, I’ll describe why we care– not only in trinary star systems, but three-body interactions also matter in rich clusters. I’ll describe how we’re able to solve the 3-Body problem and figure out the orbits of stars in such system, and give a demonstration of a working computer that actually solves the system in Second Life, right before your eyes….

The talk will be at the MICA Large Amphitheater in Second Life. Remember, a Second Life account is free!

In related news, I’ve now uploaded the slides to all of my previous talks to the MICA website.

Comments Off

Posted in Physics & Astronomy, Science, Second Life, Second Life Events |

“The Stars in a Galaxy” — talk Saturday at 10AM PDT / 17:00 UT in Second Life

Posted on September 4th, 2009 — permalink

I’ll be giving the latest installment of my the regular talk series “Dr. Knop Talks Astronomy” (usually, but not always, given by me) in Second Life tomorrow (Saturday) morning. This time I’ll be talking about the stars that make up a galaxy:

We now know that most of the mass of a typical galaxy is Dark Matter. But, when you look at an image of a galaxy in optical or near-infrared light, the light you’re seeing comes from the stars. It turns out, however, that the stars that are responsible for most of the light you see are not representative! Most of the stars in a galaxy, and indeed most of the stellar mass of a galaxy, aren’t the ones emitting the light that you see in a typical image. In this talk, I’ll describe what we know about the kinds of stars that one finds in a typical galaxy. How typical is the Sun? What are the stars that we’re mostly seeing when we look at a galaxy? And what makes up most of the stars in a galaxy?

Drop by and see us in the StellaNova Large Amphitheater in Second Life. Second Life accounts are free; you can join at the registration portal offered by the SciLands.

This talk will use Second Life Voice.

3 Comments

Posted in Physics & Astronomy, Science, Second Life, Second Life Events |

I give regular talks in a series entitled “Dr. Knop Talks Astronomy” as part of

I give regular talks in a series entitled “Dr. Knop Talks Astronomy” as part of